How to make your retirement account withdrawals work best for you

November 2025, Make Your Plan

- Key Insights

-

- There are alternatives to the conventional strategy of drawing on a taxable account first, followed by tax-deferred accounts (e.g., Traditional individual retirement accounts) and then Roth accounts.

- A variety of strategies can be employed at different phases of retirement, such as filling low tax brackets, taking tax-free capital gains, and executing Roth conversions.

- Coordinating a withdrawal strategy and a Social Security claiming strategy can drive even more tax efficiency than either approach alone.

- If planning to leave an estate to heirs, consider which assets will ultimately maximize their after-tax value.

Retirement should be a time of freedom, not financial stress. Yet for many, the shift from saving to spending brings unexpected challenges.

Hi, I'm Roger Young, a CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER professional and thought leadership director at T. Rowe Price. Today I'll walk through three scenarios that reveal just how powerful a thoughtful withdrawal strategy can be.

With the right approach, you can lower your lifetime tax bill, potentially add years to the life of your retirement portfolio, and increase the legacy you leave to loved ones.

Conventionally, you would draw down taxable accounts first, then tax-deferred, and finally, Roth. But following that strict order can end up costing you. Early on in our first scenario, taxes feel low, but when taxable assets run out, large IRA or 401(k) withdrawals can push you into higher brackets.

By modestly taking from tax-deferred accounts early, before claiming Social Security and staying in the 10% or 12% bracket, you smooth your tax burden. That can save tens of thousands and boost your legacy.

Our second scenario is a single retiree with most savings in tax deferred accounts. In this situation, a “tax torpedo” can spike your taxes when Social Security becomes taxable. By executing strategic Roth conversions early, before claiming benefits, you shrink the taxable portion of your income and reduce the risk of running out of money.

And for our third scenario, if your heirs face higher tax brackets, consider drawing down your tax-deferred accounts and preserving taxable assets. Thanks to the step up in basis at death, a bit more tax now can translate into a significantly larger after-tax inheritance.

These strategies aren't guesswork. They're backed by years of research on tax efficiency and withdrawal sequencing. At T. Rowe Price, our advisors use tools like IncomeSolverTM to stress test your plan, optimize income, minimize taxes, and leave the legacy you intend.

Partner with a T. Rowe Price Retirement Advisory ServiceTM advisor today by visiting troweprice.com/getaplan.

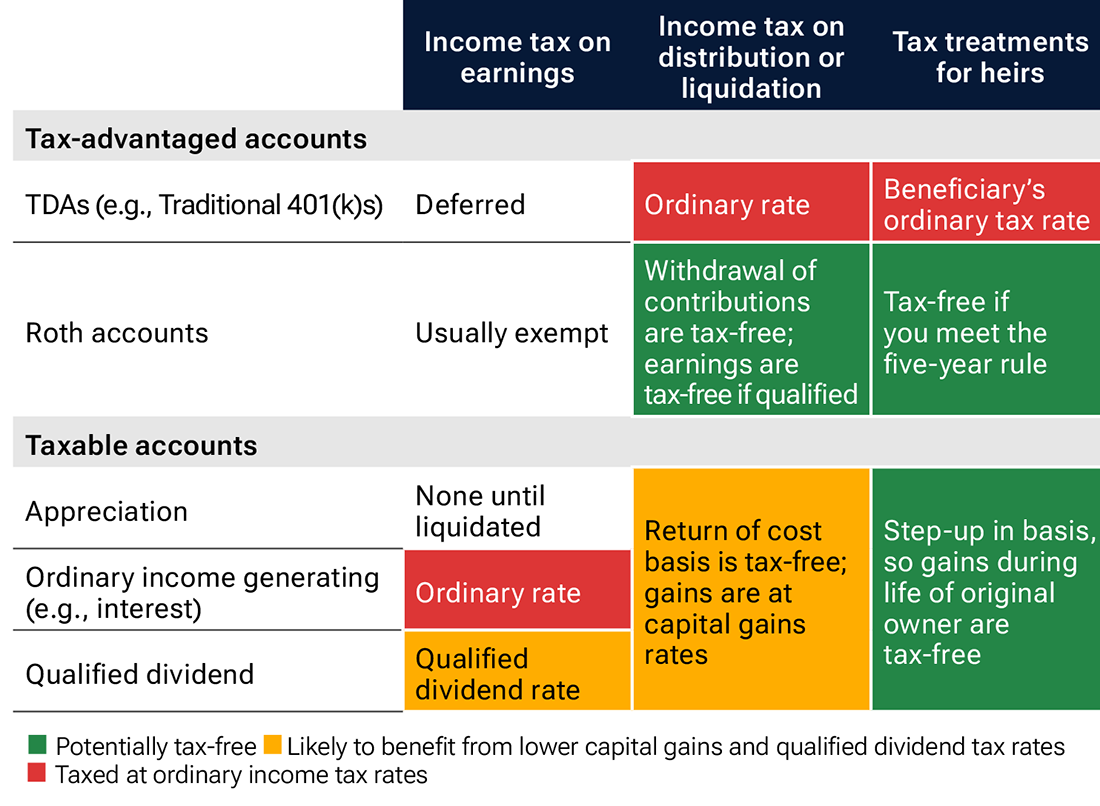

Many people will rely largely on Social Security benefits and tax-deferred accounts (TDAs)—such as Traditional individual retirement accounts (IRAs) and 401(k) plans—to support their lifestyle in retirement. However, a sizable number of retirees will also enter retirement with assets in taxable accounts (such as brokerage accounts) and Roth accounts. Deciding how to use that combination of accounts to fund spending is a decision likely driven by tax consequences, because distributions or withdrawals from the accounts have different tax characteristics (see Figure 1).

“Investors with more than one type of account can do better than following the conventional wisdom strategy when withdrawing funds in retirement.”

William Reichenstein Ph.D., Thought Leadership Director

Tax characteristics of different assets

(Fig. 1) The tax treatment varies significantly by type of account

close

close

A commonly suggested approach, which we’ll call the conventional wisdom strategy, is to withdraw from taxable accounts first, followed by TDAs and, finally, Roth accounts. There is some logic to this approach:

- If you draw from taxable accounts first, your TDAs have more time to grow tax‑deferred and your Roth accounts have more time to grow tax-exempt.1

- Leaving Roth assets until last provides potential tax-free income for your heirs.

- It is relatively easy to implement.

Unfortunately, the conventional wisdom strategy may result in income that is unnecessarily taxed at high rates. In addition, this approach does not consider the tax situations of both retirees and their heirs.

This paper considers two broad objectives that retirees may have and how to achieve these through strategic account withdrawals:

- Spending more in retirement (either annually or by extending the life of their portfolio)2

- Bequeathing assets efficiently to their heirs

In the first objective, the focus is on the retiree, not the heirs. For people focused on the second objective—leaving an estate—the withdrawal strategy can include techniques to minimize taxes across generations.

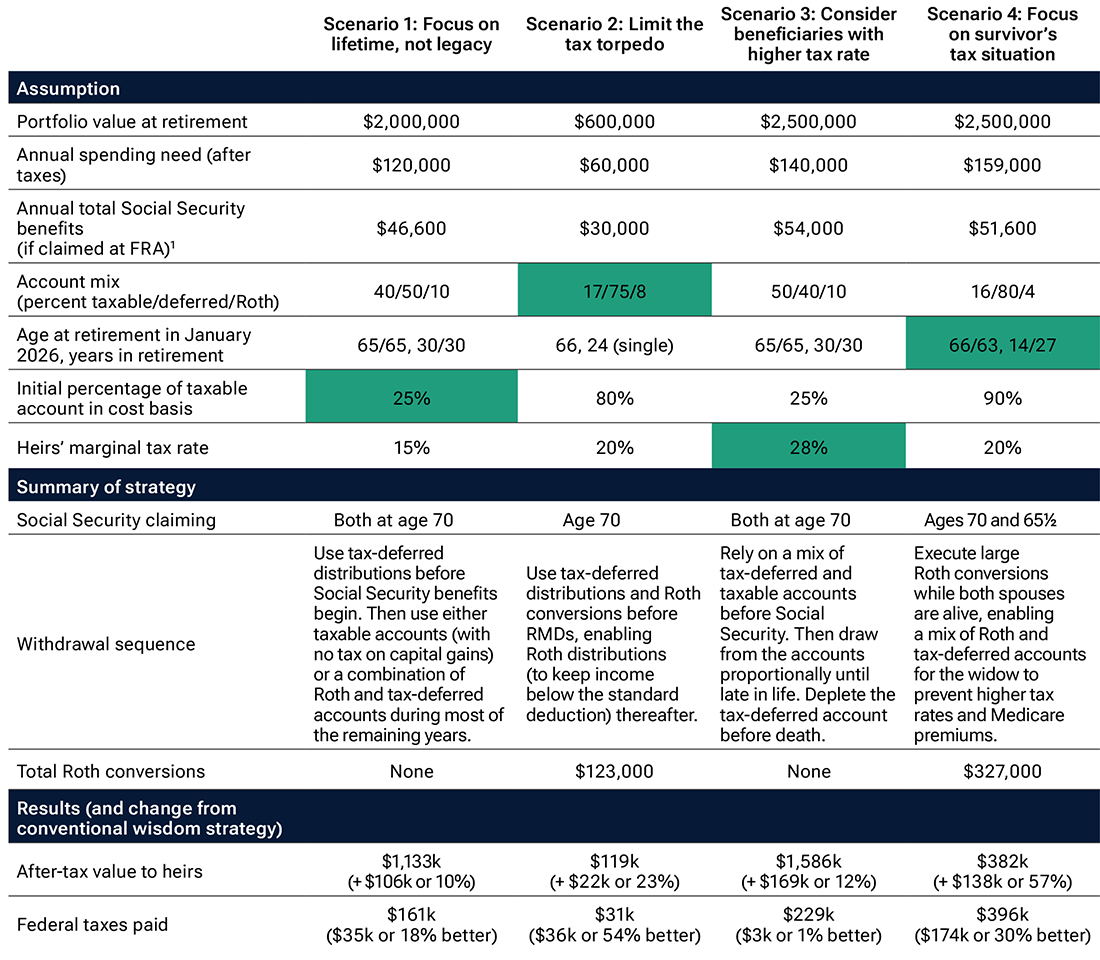

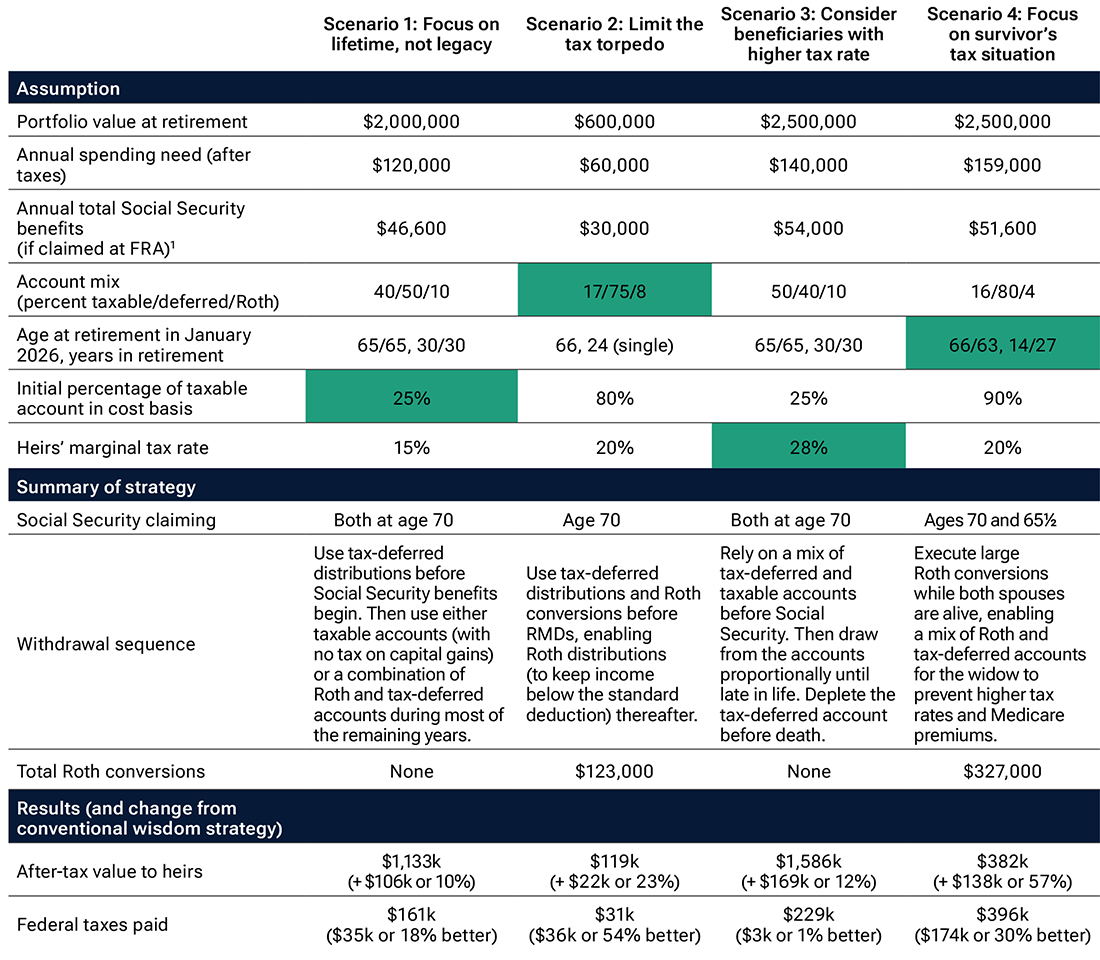

So what can investors do, and how can advisors navigate these conversations? We evaluated different withdrawal strategies for a variety of situations and summarized the key techniques for four scenarios (types of people). Our evaluation was based on the assumptions (see the Appendix for further details), key among them:

- Because the results depend so heavily on federal taxes, we took into account tax rules on Social Security benefits, qualified dividends, long-term capital gains (LTCG), and ordinary income. See “What to Know About Social Security Benefits and Your Taxes,” as well as the second example in this paper, for further discussion of how these tax effects are interrelated.

- All of these households begin retirement at the start of 2026.

- The household uses the standard deduction.3

- State taxes and federal estate taxes are not considered.

- All accounts earn the same constant rate of return before taxes.

- All amounts are expressed in today’s dollars (USD) and generally rounded to the nearest $1,000.

Scenario 1: Retirees focused on their spending and taxes rather than on leaving a legacy

Strategy: Carefully choose the timing of TDA distributions to take full advantage of income at lower ordinary and capital gains tax rates.

Many people—including a good number with household incomes above the U.S. median—may be in a low tax bracket in retirement. They are probably more concerned about meeting their own needs than with leaving an inheritance. And even if they might leave a legacy, they may not be too worried about the taxes their beneficiaries will pay. Those who have done a solid job of saving in different accounts can probably withdraw funds more tax efficiently than they could by following the conventional wisdom strategy.

When following the conventional wisdom strategy, you start by relying on taxable account withdrawals and Social Security benefits (if already claimed). Since withdrawals from taxable accounts are partly, if not entirely, tax-free and Social Security benefits are never fully taxed, you may find yourself paying little or no federal income tax early in retirement before required minimum distributions (RMDs) begin. That sounds great—but you may be leaving some low-taxed income “on the table.” And then after RMDs kick in, you may be paying more taxes than necessary.

One potentially better approach is to spread out ordinary income from TDA distributions across more years. For example, this income could fill the “0% bracket,” where adjusted gross income (AGI) is less than deductions, or use the 10%–12% brackets. Another strategy is to prioritize TDA distributions before Social Security benefits begin and then rely more on distributions from taxable accounts and/or Roth accounts.

To illustrate this, scenario 1 represents a married couple. Both spouses turn 65 in January 2026 and live to age 95. That is, they plan for a lifetime of 95 years, in case they live that long. They can maintain their lifestyle by spending $120,000 per year (after taxes). Their total annual Social Security benefits would be $46,600 if claimed at their full retirement age (FRA), with similar amounts for each spouse. Their retirement portfolio of $2 million includes 40% in taxable accounts, 50% in TDAs, and 10% in Roth accounts. The cost basis in their taxable account is only 25% of its value, so selling those investments will result in meaningful capital gains. The couple expects their beneficiaries to be in the 15% bracket, so minimizing their taxes is not a top priority.

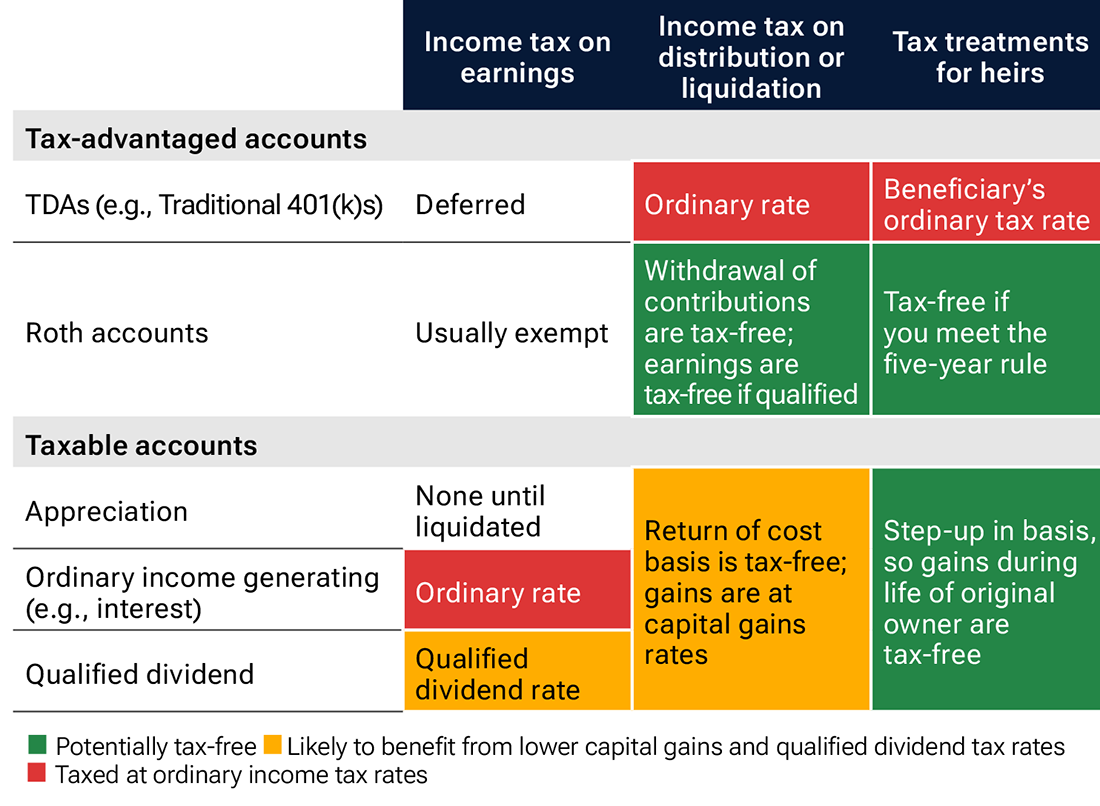

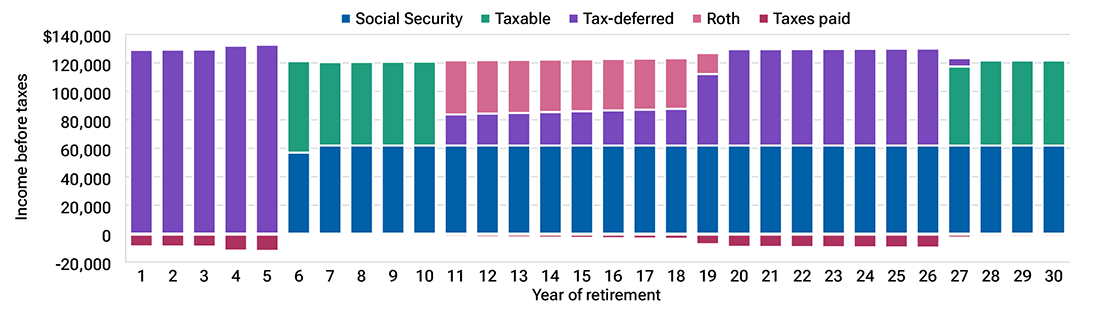

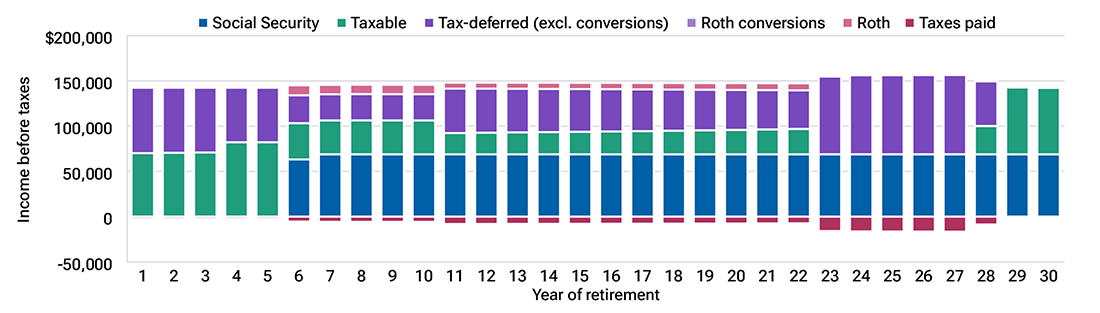

Figure 2 shows how this couple would meet their spending needs using the conventional wisdom strategy. The illustration assumes both spouses will claim Social Security at age 70, which we have identified as their best strategy.4 Taxes paid are shown as negatives in red. Throughout this paper, we will use these graphs to help explain strategies and show the tax impact.

Sources of retirement income for scenario 1, under conventional wisdom strategy

(Fig. 2) This approach results in unnecessary taxes in the latter part of the couple’s retirement years

close

close

With this approach, the couple first exhausts the taxable account (green) and then the TDA (purple). In this case, they do not need to draw upon Roth assets. In the first five years, before they claim Social Security benefits, they have negative taxable income—that is, their AGI is less than their standard deduction. So they pay no federal income tax. For the next five years, they pay less than $1,000 per year in taxes. However, once they run out of money in their taxable account, they pay over $9,000 per year in federal taxes for the majority of their retirement.

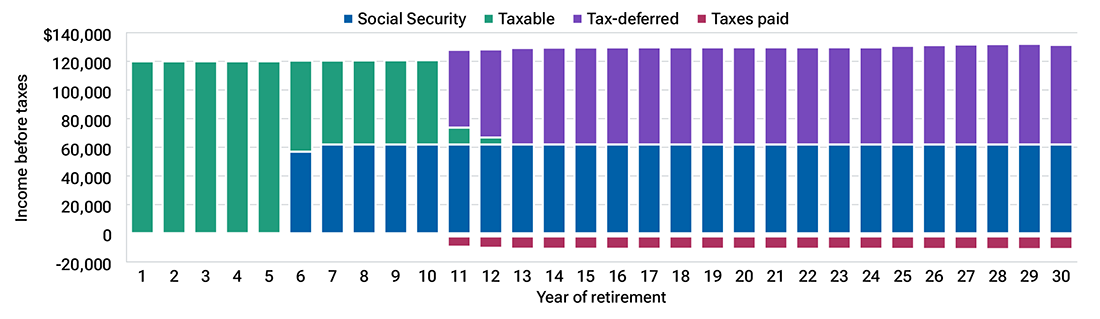

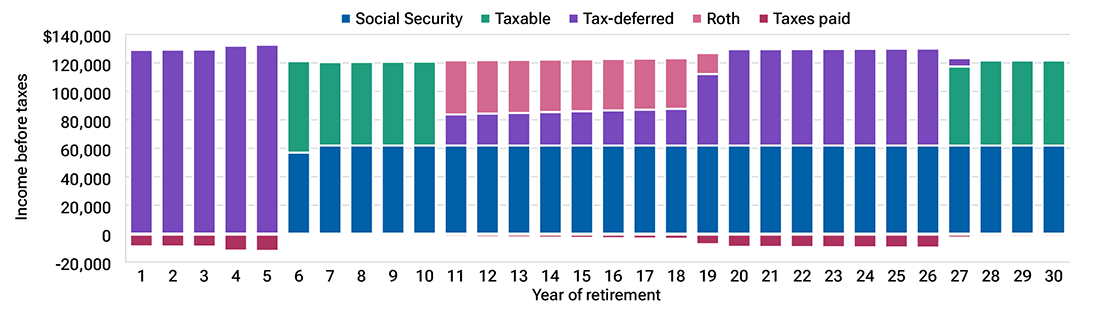

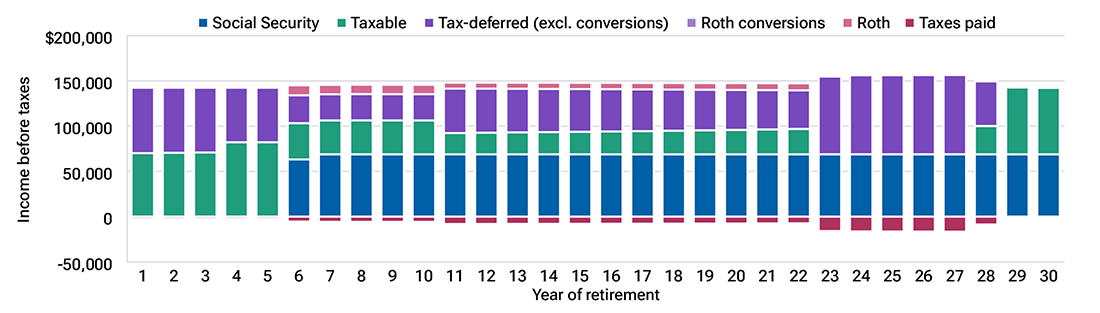

If they follow a more tax-efficient strategy, the withdrawals (shown in Figure 3) are quite different. In this strategy, they use TDA distributions early and then combine them with Roth distributions in a later phase of retirement.

Sources of retirement income for scenario 1, under a TDA-timing method

(Fig. 3) By carefully timing TDA distributions, the household pays less tax than under the conventional wisdom strategy

close

close

More specifically, the strategy relies on TDA distributions in the 10% and 12% brackets in the first five years, before Social Security benefits begin. (See scenario 2 for more discussion about how those benefits are taxed.) Then it uses taxable account distributions to take advantage of untaxed capital gains until they start RMDs in the year they turn 75. At that point, spending needs not met by RMDs are satisfied with tax-free Roth distributions until that account is exhausted, then with either the TDA or the taxable account.

This strategy incurs as much as $13,000 of taxes in the first five years but less than $4,000 in 20 years of their 30-year planning period. As a result, the better strategy saves $35,000 in taxes versus the conventional wisdom strategy.

Our methodology aims to maximize the after-tax legacy (if the household’s spending needs are met). This after-tax legacy is the sum of all accounts after the death of the last spouse but where TDA balances are reduced by an estimate of the heirs’ marginal tax rate. Using this strategy, the couple’s beneficiaries get a $106,000 larger after-tax inheritance than with the conventional wisdom strategy. While this may not be the couple’s top priority, the strategy delivers the highest after-tax legacy. Even though it does not leave any tax-free Roth assets to the next generation, as the conventional wisdom strategy does, all of the remaining assets are in taxable accounts that receive the step-up in basis. (See scenario 3 for further discussion of the step-up; also see the assumptions and results for all examples in the Appendix.)

Since this couple has a significant taxable account with unrealized gains, it’s also important to understand the impact of capital gains taxes. Even though this is a fairly affluent couple, their income level does not result in any capital gains taxes.

Key insight: Moderate-income people with multiple types of accounts may want to draw down Roth assets along with TDAs to extend the period when they are in a low tax bracket.

Scenario 2: People who may be affected by high marginal tax rates on Social Security benefits

Strategy: Use Roth conversions early in retirement before Social Security benefits begin to limit income taxed at high marginal tax rates in later years.

In the first scenario, the couple did not need to use Roth conversions to keep their marginal tax rates reasonable throughout retirement. In other situations, however, investors may rely more heavily on TDA withdrawals and Social Security benefits. In those cases, the complex calculation of taxes on Social Security benefits becomes important, especially for people who are not particularly wealthy. Therefore, it can make sense to convert some TDAs to a Roth account early in retirement.

“Selling appreciated assets held in taxable accounts in low-income years could eliminate capital gains taxes if those gains would eventually be taxed upon sales later in life .”

William Reichenstein, Ph.D. Thought Leadership Director

Consider scenario 2, a single person retiring at age 66 (born in December 1959) who plans for a life expectancy of 90 years. Of her $600,000 in assets, 75% ($450,000) is in tax-deferred accounts, $100,000 is in taxable accounts (with a cost basis of $80,000), and $50,000 is in Roth accounts. Planned spending is $60,000 per year, and her annual Social Security benefits would be $30,000 if claimed at her FRA.

If she uses the conventional wisdom strategy, she will be in the 12% federal bracket during nearly all of the years where her TDAs are drawn down. That tax bracket, however, does not tell the full story.

The amount of Social Security benefits subject to taxes depends on how much “combined” (also referred to as “provisional”) income someone has. For most taxpayers, that number is essentially half of the Social Security benefits plus all other income included in AGI. At low levels of combined income, no Social Security benefits are taxed. But as combined income increases, the amount of Social Security income that is taxable increases: first at 50% of incremental income, then at 85%. At most, 85% of benefits are taxable. Therefore, for this person in the 12% bracket, there is a range of income where each additional dollar of income causes an additional $0.85 of Social Security benefits to be taxable. So, taxable income rises by $1.85. Thus, the marginal tax rate on that dollar of income may be 22.2%, (12% tax bracket x $1.85). Such spikes in marginal tax rates caused by the taxation of Social Security benefits are sometimes referred to as the “tax torpedo.” Avoiding significant income subject to marginal tax rates that are 185% of the tax bracket can meaningfully improve the outcome.

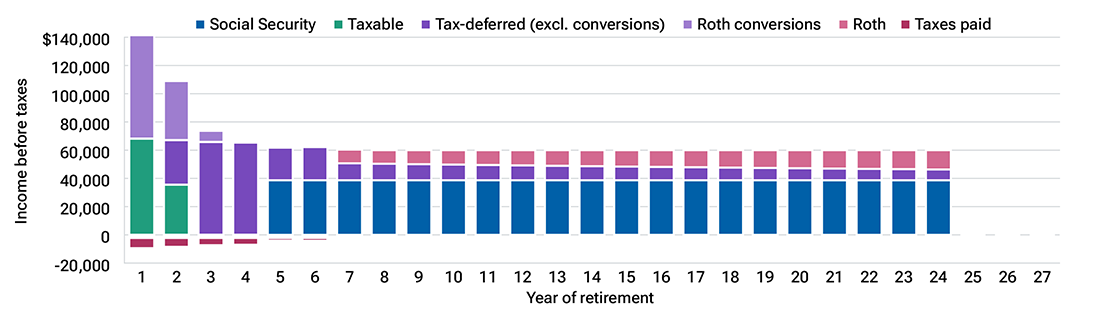

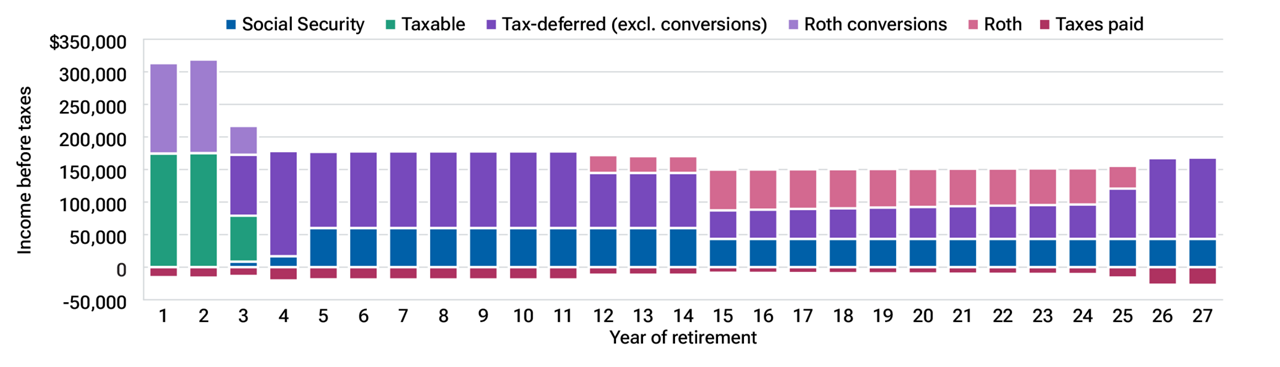

The best strategy we found is depicted in Figure 4. It starts by employing a total of $123,000 of Roth conversions within the 12% bracket over the first three years, before she claims Social Security benefits at age 70. For the next three years, spending is satisfied using TDA distributions and Social Security benefits.

Sources of retirement income for scenario 2, utilizing a Roth conversion strategy

(Fig. 4) Converting tax-deferred assets to Roth accounts at an opportune time can help reduce taxes on Social Security benefits

close

close

Once RMDs begin in year seven, this strategy combines TDA distributions with Roth account distributions. Due to the early‑year Roth conversions, she has enough Roth assets to completely avoid federal income taxes for the rest of her retirement years.

By making Roth conversions in years before Social Security benefits begin, this strategy results in only 24% of Social Security benefits being taxable, on average. That taxable portion is small enough that even when added to the taxable TDA distributions, the total is below the standard deduction. In contrast, an average of 52% of Social Security benefits is taxable for the conventional wisdom strategy. Largely because of that, lifetime taxes are $36,000 lower using the better strategy compared with the conventional wisdom strategy, and the after-tax legacy improves by $22,000. (See the Appendix for further details.)

Key insight: Roth conversions aren’t only for people in high tax brackets who will leave large estates. In some cases, they can also help people at lower income levels reduce taxes on their Social Security benefits.

Scenario 3: People who expect to leave money to beneficiaries with higher tax rates

Strategy: Consider your heirs’ tax situations when deciding whether to leave them tax-deferred assets or Roth assets. Also consider preserving taxable assets for the step-up in basis.

People who have accumulated significant assets may have confidence that they are unlikely to run out of money. Therefore, they can plan a strategy with their heirs in mind. These people aren’t necessarily ultra-wealthy, but they have been strong savers relative to their income or spending needs. While these households may have a relatively small portion of assets in Roth accounts, any Roth assets they do have can be beneficial in planning.

A strategy to consider involves choosing whether to take TDA distributions beyond your RMDs. When accumulating assets, it usually makes sense to choose between making contributions to TDAs or Roth accounts based on whether you think your tax rate will be lower or higher in retirement than in your preretirement years.

Similarly, to leave your heirs the largest after-tax inheritance, consider their potential tax rate. If it’s higher than yours, it may be better to leave them Roth assets or taxable account assets and draw on TDA assets for your own spending needs.

“People leaving an estate should consider holding on to stock investments that will eventually go to their heirs in taxable assets, so their heirs get the step-up in basis—that is, the tax-free gains.”

William Reichenstein, Ph.D. Thought Leadership Director

Of course, there are some challenges with implementing this approach. First, it can be difficult to predict your heirs’ tax rates 30 years down the road. Second, your own marginal tax rate can change over the course of your retirement. That said, if your heirs’ tax situation is even somewhat predictable, it can be a factor to consider.

An important facet of this strategy to consider is preserving taxable assets. The cost basis for inherited investments is the value at the owner’s death. This is known as a step‑up in basis, and it effectively makes gains during the original owner’s lifetime tax-free for heirs. (A spouse inheriting a jointly held investment may receive a partial or full step-up, depending on laws of their state.) This can be a major benefit for people with wealth that won’t be spent in their retirement years.

There are four major factors that determine the attractiveness of holding taxable assets for the step-up compared with preserving Roth assets:5

- Cost basis, as a percentage of value (lower basis favors holding the taxable assets);

- The tax rate on capital gains and dividends (higher rate favors holding the taxable assets);

- Life expectancy of the owner (holding taxable assets becomes more attractive closer to the end of life); and

- The investment’s dividend yield (lower dividend yield favors holding the taxable assets).

One tricky part about this decision is that the capital gains tax rate depends on your taxable income. Therefore, it can change based on how you use different accounts to meet your spending needs. As we discussed in the first scenario, some people can take advantage of untaxed capital gains, especially before RMDs. To the extent that gains are untaxed, there is no benefit in holding those assets for the step-up. Another caveat is that we assume the same investment returns for all accounts; if your low-basis taxable investment has lower growth potential or higher risk, holding it obviously becomes less attractive.

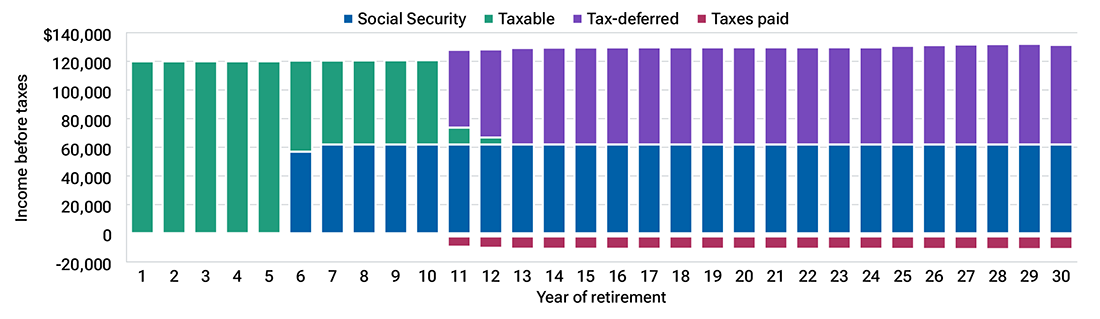

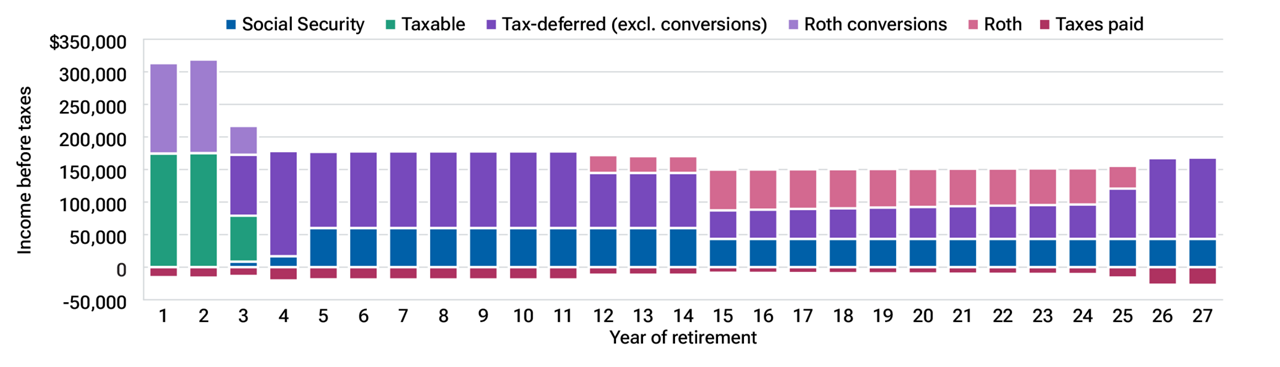

For scenario 3, some facts are similar to the first example: This couple, both born in January 1961, start their retirement at age 65 in January 2026, and they plan for a life expectancy of 95 years. They have $2.5 million in assets: 40% in tax-deferred accounts, 50% in taxable accounts (with a 25% cost basis), and 10% in Roth accounts. They plan to spend $140,000 per year and would have total annual Social Security benefits of $54,000 if they claim at FRA (with similar amounts for each spouse). Based on these facts, they are highly likely to leave assets to beneficiaries, who we assume will have a marginal tax rate of 28%. That is higher than the couple’s top rate even under the conventional wisdom strategy. Therefore, it makes sense for this couple to draw down their TDA assets before death. As illustrated in Figure 5, the best strategy carefully chooses when to take those TDA distributions.

“Drawing down TDAs during your lifetime can help your highly taxed heirs later. But proceed with caution.”

Roger Young, CFP® Thought Leadership Director

Sources of retirement income for scenario 3, drawing down tax-deferred accounts before death

(Fig. 5) Heirs in a high tax bracket can benefit from the step-up on taxable investments rather than inheriting tax-deferred accounts

close

close

The couple’s best Social Security claiming strategy is for both spouses to begin benefits at age 70. Before that point, taxable account withdrawals would be supplemented by TDA distributions up to the top of the 10% bracket. Over the next 17 years, the strategy supplements Social Security (and eventually RMDs) with a proportional mix of all account types, which keeps the household comfortably in the 12% bracket. Thereafter, spending needs are met by TDA distributions to deplete the accounts shortly before death. That leaves taxable accounts to meet their spending needs at the very end, and the remaining taxable account assets pass to their heirs with the benefit of the step-up.

This strategy results in only slightly lower taxes during the couple’s lifetime compared with the conventional wisdom strategy. However, due to the beneficiaries’ higher tax rate and timing of taxes paid, the after-tax legacy of the recommended strategy is 12%, or $169,000 higher than with the conventional wisdom strategy.

There is somewhat of a spike in taxes for this strategy in years 23 through 27, when the TDA is being drawn down. That suggests a few caveats about using this type of approach:

- A retiree will want to be highly confident they’re not going to run out of money.

- They should also be pretty sure their heirs will have higher marginal tax rates.

- There are good reasons to keep some tax-deferred assets in reserve. For example, if a person incurs large, deductible medical expenses later in life, they can use those deductions to offset tax-deferred distributions.6

Key insight: Techniques to optimize heirs’ after-tax inheritance are not simple to evaluate, but they’re worth considering if an individual expects that their heirs will have significantly different tax rates than them.

Scenario 4: An affluent couple, where one spouse is expected to outlive the other by several years

Strategy: Make large Roth conversions while both partners are still alive, to avoid higher taxes and higher Medicare premiums for the survivor after the death of the first spouse.

So far, our two examples for couples have assumed both spouses die at the same time. While we don’t know how long we will live, there is a significant chance one spouse (often a wife) will live many years longer than the other. That’s particularly true if there’s a large gap in their ages or a large difference in their levels of health.

When a spouse dies, many things happen from a financial perspective. In general, Social Security benefits decrease to the higher of the two spouses’ benefits. Typically, the surviving spouse is the beneficiary of TDAs. That can change the calculation of RMDs but perhaps not dramatically. And spending levels probably decrease somewhat, but many fixed costs, such as housing, could stay the same.

After the year of death, a survivor (who doesn’t remarry) will start filing taxes as a single individual rather than as part of a married couple filing jointly. Currently, the tops of the first five tax brackets for singles are half as high as for married couples filing jointly. Since total spending (and income) will likely fall by much less than 50%, the survivor can easily be pushed into a higher bracket. Similarly, since the first four income threshold levels where Medicare premiums spike are half as high for singles as for married couples, the surviving spouse may pay sharply higher Medicare premiums beginning three calendar years after the death of the first spouse.

For scenario 4, the husband (age 66 at retirement) is three years older than his wife (63). His life expectancy is 80, whereas hers is 90, so she is expected to have a 13-year survivorship period. Their $2.5 million portfolio is largely (80%) in tax-deferred accounts, with 16% in taxable accounts and 4% in Roth accounts. The cost basis in the taxable account is 90% of its value. They plan to spend $159,000 per year, but that amount drops by 10% when the husband dies. Unlike the other scenarios, the husband’s annual Social Security benefit ($33,600 at FRA) is much larger than the wife’s ($18,000).

In a case like this with an expected long survivorship period, it is very important that the higher earner wait until age 70 to start Social Security benefits. Unlike the other examples, in this scenario, our software recommends that the lower earner claim earlier, starting at age 65 and six months, because benefits based on her earnings record will cease at the death of the first spouse.

Using the conventional wisdom strategy, the widow would rely on TDA distributions to meet her spending needs. That pushes her into the 24% bracket and causes her to pay higher Medicare premiums (income-related monthly adjustment amounts, or IRMAAs) for 11 years.

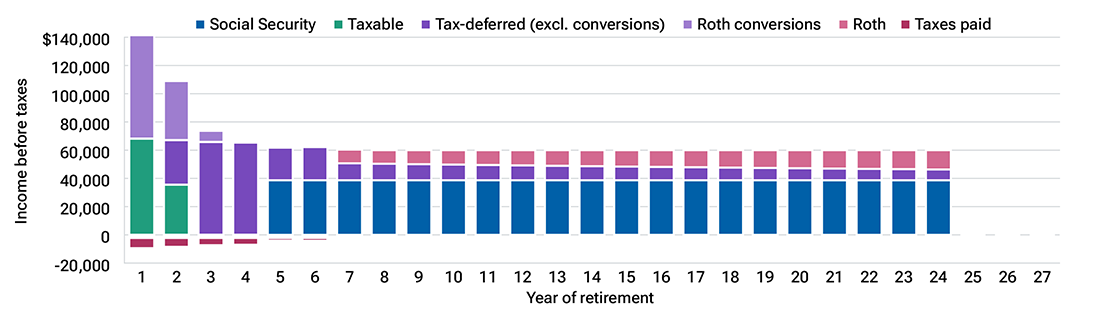

The best strategy we identified uses an aggressive Roth conversion approach in the first three years of retirement, while both partners are still alive (see Figure 6). It calls for conversions up to the top of the 12% bracket. The couple relies on taxable, and then TDA, assets to fund spending and pay for taxes on a total of $327,000 of Roth conversions.

Sources of retirement income for scenario 4; Roth conversions to benefit a surviving spouse

(Fig. 6) When one spouse is expected to outlive the other by many years, Roth conversions can prevent a sharp increase in income taxes and Medicare premiums for the surviving spouse

close

close

The strategy then relies on TDA distributions (staying below IRMAA thresholds) for eight years. From that point on, the strategy aims to stay within the 12% bracket through a combination of TDA and Roth account distributions. For the three years until the husband’s death, that doesn’t require large distributions from the Roth accounts. However, once he dies and she files as a single taxpayer with the lower tax bracket thresholds beginning in year 15, she needs to rely more on Roth account distributions. Those distributions were made possible by the large Roth conversions early in retirement, while both partners were still alive.

Despite significant taxes paid in the early years, the recommended Roth conversion strategy would incur $174,000 lower lifetime income taxes than in the conventional wisdom strategy. In addition, total Medicare premiums would be $25,000 lower using the Roth conversion strategy. The Roth conversion strategy would leave an after-tax legacy of $382,000, which is an improvement of $138,000 compared with the conventional wisdom strategy.

Key insight: An aggressive Roth conversion strategy in early retirement years when both spouses are still alive requires some serious thinking due to the large up-front tax burden, but it can pay off handsomely when one spouse outlives the other by several years.

Other observations and considerations

The examples we’ve shown highlight the benefits of strategies for specific situations. In addition to these examples and techniques, retirees should consider the following:

- The Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement (SECURE) Act of 2019 limited the ability to stretch distributions from Inherited IRAs and retirement plan accounts over time. Rather than taking RMDs over their expected lifetime, most beneficiaries will need to draw down the account fully within 10 calendar years of the original owner’s death.7 Therefore, a large inherited TDA may force a beneficiary to pay a higher marginal tax rate, so it is increasingly important to understand the tax situation of potential beneficiaries. Consider leaving different types of accounts to different beneficiaries (e.g., leave Roth accounts or taxable accounts to higher‑income children and leave TDAs to lower-income children). In addition, dividing retirement accounts among several beneficiaries can reduce the risk of higher taxes due to the 10-year rule.

- The 2025 One Big Beautiful Bill Act contains many provisions that affect retirees, including a new $6,000 deduction for individuals 65 and older that expires after 2028. That provision and other deductions could affect withdrawal strategies—for example, by enabling larger Roth conversions in low tax brackets while the deductions are in effect.

- If an investor has a significant portion of assets in TDAs (as in all of our examples), RMDs significantly limit their flexibility after the relevant age. As a result, retirees need to plan early and take advantage of the pre-RMD years for most strategies to have a significant impact. Due to the taxation of Social Security benefits (i.e., the tax torpedo), it is often important to plan a strategy that begins before the household claims their Social Security benefits.

- This paper shows results for the conventional wisdom strategy assuming the same (best) Social Security claiming decisions as the recommended withdrawal strategy. However, many people think about claiming Social Security early, and they should be aware that there is often synergy generated when they coordinate their Social Security claiming decision with their withdrawal strategy. In some of the cases shown, delaying Social Security not only increases lifetime benefits, but it also enables households to execute Roth conversions at attractive tax rates that avoid the tax torpedo.

- We assumed all accounts have the same investment return. In real life, it is important to consider asset allocation and location across the accounts. Using TDAs or Roth accounts for rebalancing or allocation changes, if possible, may minimize tax-triggering events in the taxable account.

- We assumed a fairly tax-efficient taxable account composed of stocks or stock funds. If an individual’s taxable account includes investments such as bonds that generate ordinary income, they generally want to liquidate those investments sooner. That makes the point above about managing asset allocation and location particularly important.

“It’s important to plan before RMDs limit your flexibility.”

Roger Young, CFP® Thought Leadership Director

- State income taxes should also be considered, but they may not be a driving factor in an investor’s decision. Most states do not tax Social Security income, and some exclude at least a part of pension benefits or retirement account distributions. Those provisions could put an individual in a low state tax bracket in retirement. That would make it slightly more preferable for them to take TDA distributions if their heirs will be subject to higher marginal tax rates.

- Taxes on different types of retirement income are complicated and interrelated. Therefore, we highly recommend consulting with a tax or financial professional.

- We assumed constant spending (in today’s dollars). To deal with major changes in spending (e.g., major purchases, medical expenses), having a borrowing source, such as a home equity line of credit, may be useful. That liquidity may enable an individual to avoid large distributions or withdrawals that would significantly increase their taxes.

Conclusion

Retirees with solid savings and a mix of investment account types are well positioned to take advantage of the tax code. Rather than settling for the conventional wisdom withdrawal strategy, they can benefit from one or more of these strategies:

- Drawing from TDAs to take advantage of a low (or even 0%) tax bracket, especially before RMDs begin.

- Executing Roth conversions early in retirement to reduce future RMDs and enable the household or beneficiaries to avoid high marginal tax rates (including the tax torpedo).

- Selling taxable investments when income is below the taxation threshold for LTCG (often supplementing with tax-free Roth distributions to meet their spending needs).

- Considering heirs’ marginal tax rates when deciding between TDA and Roth account distributions (if an individual is confident there will be an estate).

- Evaluating whether to hold taxable assets until death to take advantage of the step-up in basis (again, only if the assets won’t be needed for spending in an investor’s lifetime).

Appendix

Summary of scenario assumptions and results (rounded)

(Fig. 7) Particularly important assumptions are highlighted in green

Notes: All amounts are in today’s dollars, rounded. Retirement begins January 2026. In all examples, the portfolio lasts the entire expected lifetime (for both the recommended strategy and the conventional wisdom strategy). Annual spending includes Medicare premiums without any potential income‑related premium adjustments. See full list of assumptions below.

1 For couples, Social Security benefits are assumed to be similar, except in scenario 4, where the FRA benefit is $33,600 for the husband and $18,000 for the wife.

close

close

Assumptions

(Unless otherwise noted)

- All accounts earn the same 6% constant nominal rate of return before taxes.

- Inflation is 3% annually.

- All amounts are expressed in today’s dollars. Therefore, while Social Security benefits in the analysis appropriately reflect cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs) equal to inflation, the benefits at FRA stated in this paper do not include any COLAs. Tax brackets are assumed to adjust with inflation. However, Social Security taxability thresholds do correctly reflect the fact that those are not indexed to inflation.

- Taxes are based on rates effective January 1, 2025, as well as the tax law enacted in July 2025.

- The household uses the standard deduction.

- While there are other potentially tax‑exempt sources, such as Health Savings Accounts and municipal bond interest, our analysis only considers Roth distributions (which are assumed to be qualified).

- State taxes and federal estate tax are not considered.

- All taxable investment account earnings are either qualified dividends or long‑term capital gains. Taxable investments pay a 1.5% qualified dividend yield annually as part of the return, which is reinvested.

- Gains upon liquidation of taxable investments are based on the average cost basis for the account.

- Spending requirements, including Medicare premiums before any income‑related adjustments, remain constant (in today’s dollars) throughout retirement.

- The couple has no additional sources of income beyond Social Security and investments.

- All RMDs are fulfilled, and any RMDs not needed for spending are invested in the taxable account. RMDs are based on the Uniform Lifetime Table effective beginning in 2022. Based on the assumed ages, all people in the scenarios begin RMDs at either age 73 or 75.

- Scenarios were intended to reflect reasonable Social Security benefits relative to assets and spending needs.

Roger Young, CFP®

Thought Leadership Director

Roger Young, CFP®

Thought Leadership Director

Want a personalized financial plan delivered by a T. Rowe Price Financial Advisor?

1Qualified distributions, which are tax-free generally means that the owner will be over age 59½ and the Roth account will have been open for at least 5 years.

2In terms of the analysis, longevity of the portfolio is the metric evaluated.

3We used the tax brackets (adjusted for inflation) effective January 1, 2025, as well as the tax law signed in July 2025.

4Strategies and calculations for all cases in this paper were generated by the Income SolverTM tool, which is used by advisors for the T. Rowe Price Retirement Advisory ServiceTM. While this paper will refer to the “best” strategies as identified by the tool, those are not guaranteed to be the absolute optimal solutions.

5DiLellio, James, and Dan Ostrov, “Toward Constructing Tax Efficient Withdrawal Strategies for Retirees with Traditional 401(k)/IRAs, Roth 401(k)/IRAs, and Taxable Accounts,” 2020, Financial Services Review 28 (2): 67–95. Also see Young, Roger, “Leaving Assets to Your Heirs: Could You Benefit From a Step Up in Basis?”.

6Cook, Kirsten A., William Meyer, and William Reichenstein, “Tax-Efficient Withdrawal Strategies,” 2015, Financial Analysts Journal 71 (2):16–29.

7This does not apply to some beneficiaries, such as spouses and those who are less than 10 years younger than the original owner.

Important Information

This material has been prepared for general and educational purposes only. This material does not provide recommendations concerning investments, investment strategies, or account types. It is not individualized to the needs of any specific investor and is not intended to suggest that any particular investment action is appropriate for you. Any tax-related discussion contained in this material, including any attachments/links, is not intended or written to be used, and cannot be used, for the purpose of (i) avoiding any tax penalties or (ii) promoting, marketing, or recommending to any other party any transaction or matter addressed herein. Please consult your independent legal counsel and/or tax professional regarding any legal or tax issues raised in this material.

The views contained herein are those of the authors as of October 2025 and are subject to change without notice; these views may differ from those of other T. Rowe Price associates.

This information is not intended to reflect a current or past recommendation concerning investments, investment strategies, or account types; advice of any kind; or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any securities or investment services. The opinions and commentary provided do not take into account the investment objectives or financial situation of any particular investor or class of investor. Please consider your own circumstances before making an investment decision.

Information contained herein is based upon sources we consider to be reliable; we do not, however, guarantee its accuracy. Actual future outcomes may differ materially from any estimates or forward-looking statements provided.

Past performance is not a guarantee or a reliable indicator of future results. All investments are subject to market risk, including the possible loss of principal. All charts and tables are shown for illustrative purposes only.

The T. Rowe Price Retirement Advisory Service™ is a nondiscretionary financial planning and retirement income planning service and a discretionary managed account program provided by T. Rowe Price Advisory Services, Inc., a registered investment adviser under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. Brokerage accounts for the Retirement Advisory Service are provided by T. Rowe Price Investment Services, Inc., member FINRA/SIPC, and are carried by Pershing LLC, a BNY Mellon company, member NYSE/FINRA/SIPC, which acts as a clearing broker for T. Rowe Price Investment Services, Inc. T. Rowe Price Advisory Services, Inc. and T. Rowe Price Investment Services, Inc. are affiliated companies.

T. Rowe Price Investment Services, Inc.

© 2025 T. Rowe Price. All Rights Reserved. T. ROWE PRICE, INVEST WITH CONFIDENCE, the Bighorn Sheep design, and related indicators (see troweprice.com/ip) are trademarks of T. Rowe Price Group, Inc. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners.

- 202510-4841173