- On Retirement

- Is Student Loan Debt a Barrier to Saving for Retirement?

- Employers can help their employees overcome this challenge and thrive financially.

- 2022-08-10 17:07

- Key Insights

-

- Saving for retirement is a financial goal that has steadily grown in importance for American families over the past 30 years, yet within the same span of time, student debt has emerged as a significant competing priority.

- Millennials are most burdened by student loan debt; however, Generation Xers with student loan debt are less likely than millennials to be saving for retirement.

- Workers would benefit from financial wellness programs that help them prioritize and manage day‑to‑day living expenses and debt while staying focused on short‑ and long‑term savings goals.

America is simultaneously facing retirement savings and a student loan debt crisis. The Employee Benefit Research Institute (EBRI) estimates that, collectively, Americans face a $3.83 trillion retirement savings shortfall.1 At the same time, Americans owe in excess of $1.5 trillion in government‑issued student loan debt, of which 24% was in either forbearance or default.2

Amount of money Americans owe in government‑issued student loan debt.

These are sobering statistics.

There’s evidence of unhealthy financial behaviors by savers and non‑savers alike. Our data suggest that people do not make rational decisions relative to the size of their debts or the trade‑offs necessary to reach financial goals.

The result is that the assets and liabilities workers hold will have downstream effects on their retirement readiness as they balance day‑to‑day spending, debt management, and savings goals.

Retirement savings are of increasing importance to American families, and 401(k) plans are rising as the primary savings vehicle for most workers. According to the Survey of Consumer Finances, roughly 19% of respondents cited saving for retirement as a financial goal in 1989. By 2016, that figure had risen to 30%. In contrast, saving for education was cited by only 9% of respondents in 1989 and fell to 7% in 2016.3 Yet, during this same period, the cost of a four‑year education at a public university increased approximately threefold and the cost of the same four‑year education at a private university increased twofold.4 Something has to give.

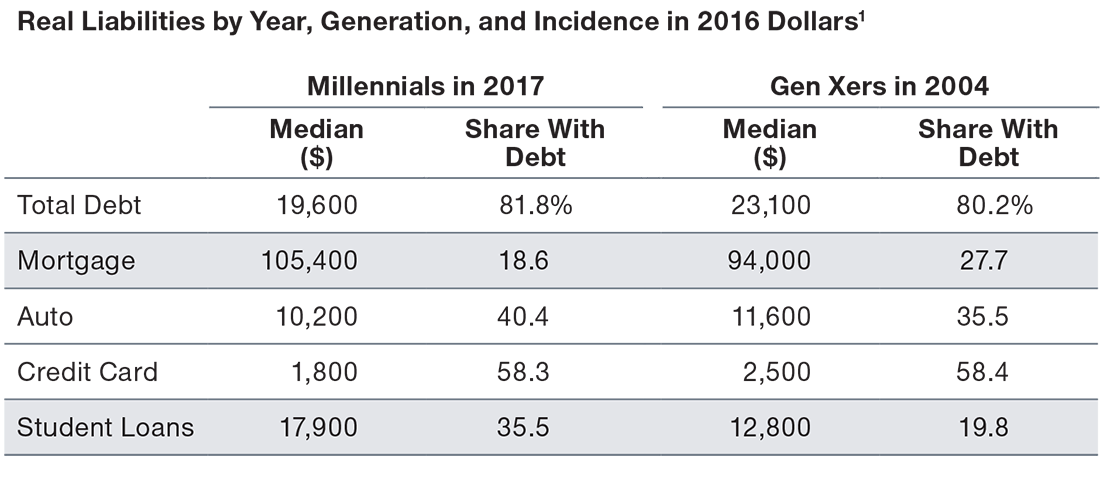

Comparing Debts of Millennials and Gen Xers

(Fig. 1) Fewer millennials owned homes and had more education debt than Gen X at the same point in their lives.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York Consumer Credit Panel/Equifax.

1 Christopher Kurz, Geng Li, and Daniel Vine, “Are Millennials Different?”

Note. The table reports various components of household liabilities for the youngest working cohort and the population in 2004 and 2017. Median values are conditional on having a positive balance.

Our research and survey revealed:

1. Age matters, but saving habits change over time.

2. Debt is holding back employees from saving more for retirement.

3. More specifically, student debt is one of many barriers to retirement savings for both plan participants and nonparticipants.

But all is not lost. Plan sponsors have an opportunity to better align their savings and benefit programs to the financial needs of their employees. The hope is that employees can take advantage of resources that can help them better organize their financial priorities in order to achieve greater financial well‑being and retirement readiness.

To better understand this issue, we’ve reviewed the relevant academic and policy research, leveraged findings from both T. Rowe Price’s 2019 Retirement Savings and Spending Study, analyzed the 2.2 million 401(k) plan accounts that T. Rowe Price recordkeeps, and, in the same year, conducted a survey of over 2,400 employees of the companies T. Rowe Price serves.

Age Matters, but Savings Habits Change Over Time

Millennials are indeed different. According to a Federal Reserve paper entitled “Are Millennials Different?” millennials had less debt than Generation X at the same point in their lives. But that fact belies a more troubling reality. When comparing the debts and assets of both millennials and Gen Xers at the same point in their lives (see Fig. 1), Gen Xers were far more likely to own homes than their millennial counterparts. In addition, the amount of debt Gen Xers took on to do so was significantly lower. There are other differences too. Millennials were almost twice as likely to have taken on student loan debt compared with Gen Xers. Further, the amount of debt was significantly higher than the previous generation.

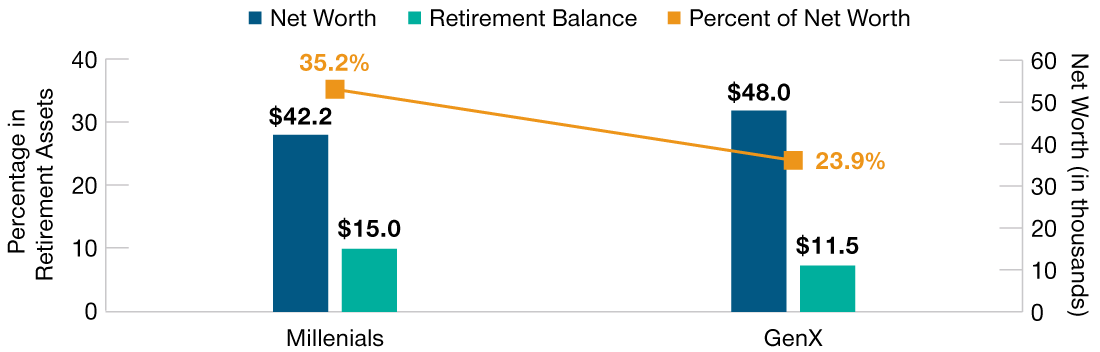

Millennials Had More Retirement Assets but Lower Net Worth

(Fig. 2) A look at median net worth and retirement balances in 2016 dollars.

Source: 2016 Survey of Consumer Finances.

Note: Median values are conditional on having a positive balance.

Not all the data are bad, but there is a caveat. Specifically, millennials had greater levels of retirement savings compared with Gen Xers (Fig. 2). However, the change in retirement savings may be attributed to the passage of the Pension Protection Act of 2006 and the widespread adoption of auto‑enrollment by employers. This resulted in workers starting to save earlier in their careers than they otherwise would under an opt‑in regime.

Still, even with this change, the median net worth of millennials was lower than that of Gen Xers due to the lack of or delay in homeownership—a major source of wealth creation. Moreover, the relative impact of homeownership is greater compared with retirement savings early in one’s career due to the use of debt to buy an asset.

Lastly, student loan and other forms of debt do impact one’s ability to save for retirement.

While household balance sheets have been changing, there are common underlying beliefs that remain constant, are resistant to change, and may be exacerbating the savings gap. For example, most people believe that debt related to education is “good” debt. Among those we surveyed, 64% “strongly agreed” or “agreed” that “Investing in education is a good investment in the future, even if it means taking on educational loans to pay for it.” That view did not materially change whether the person was participating in their employer’s plan, nor did it differ by how much was borrowed.

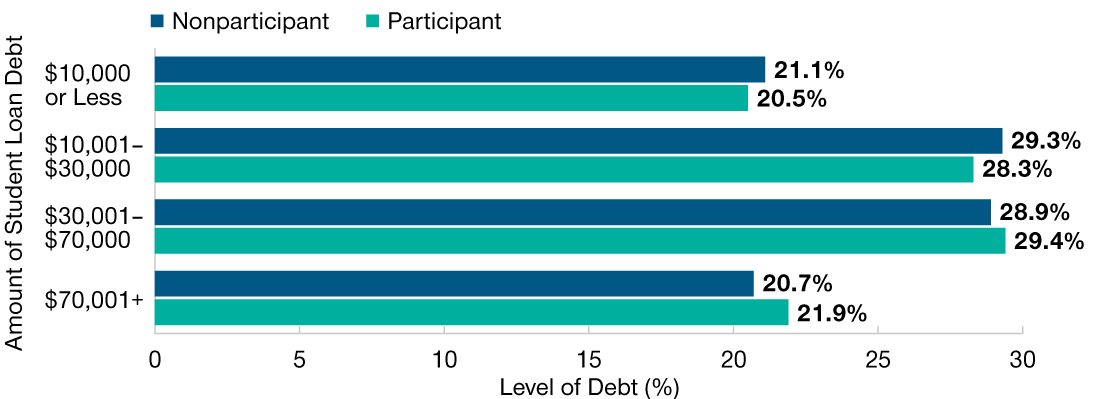

How Debt Affected Plan Participation

(Fig. 3) Higher levels of debt didn’t lead to lower 401(k) participation rates.

Source: T. Rowe Price Student Loan Survey, December 2019.

The concept of “good” debt can also help explain why the size of an individual’s student loan debts did not seem to correlate with retirement plan participation (Fig. 3). In our survey, we asked people about how much student loan debt they took on, and we saw no difference in the plan participation rates at differing levels of debt, a finding consistent with a paper authored at Boston College’s Center for Retirement Studies titled “How Does Student Debt Affect Early‑Career Retirement Saving?”5

"The data suggest that the perception of educational debt being ‘good,’ and the economic reward associated with it, is driving individuals’ willingness to take it on."

The data suggest that the perception of educational debt being “good,” and the economic reward associated with it, is driving individuals’ willingness to take it on. The underlying resiliency of this belief along with the fundamental changes to the composition and nature of debt and savings have downstream effects.

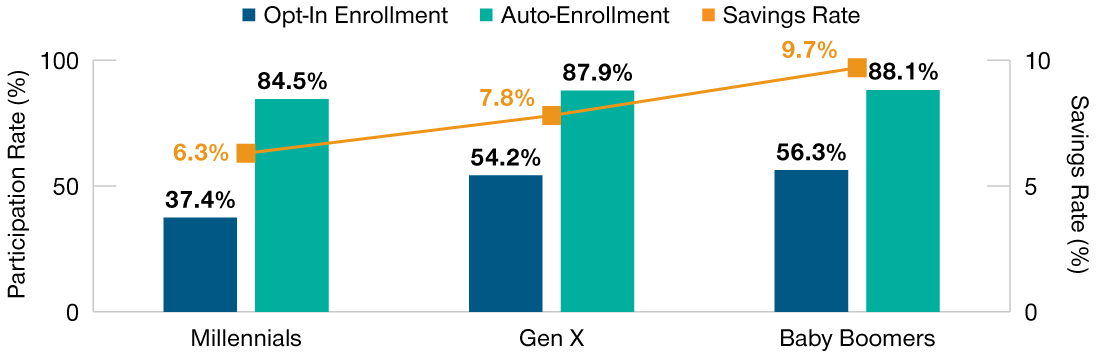

Repaying Student Loans vs. Saving for Retirement

Millennials may be saving for retirement at higher rates than preceding generations, but peak participation and savings typically do not occur until participants are within five to 10 years of retirement, regardless of whether they are auto‑enrolled or not. This is because there was a correlation between participation with age and wage growth (Fig. 4). Moreover, analysis of T. Rowe Price recordkeeping data from 2019 suggested that absent auto‑enrollment, many would not save. This is particularly true of millennials, but it applies to other generations as well. In fact, an analysis of plan participation and savings rates revealed that, if given the choice, only 54% of Gen Xers chose to participate in their employer’s retirement plan. Further, the differences between those who have been nudged to save by their employers and those who aren’t are profound.

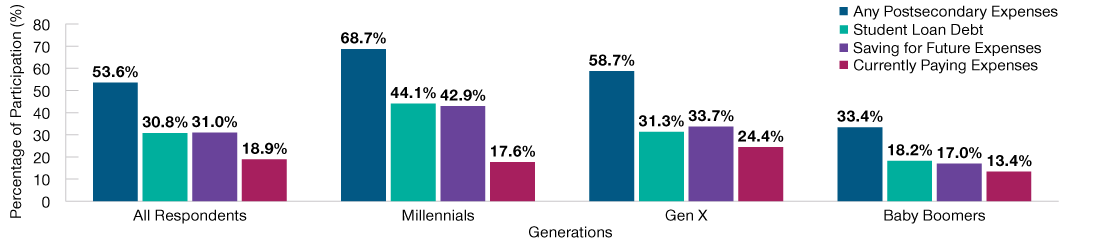

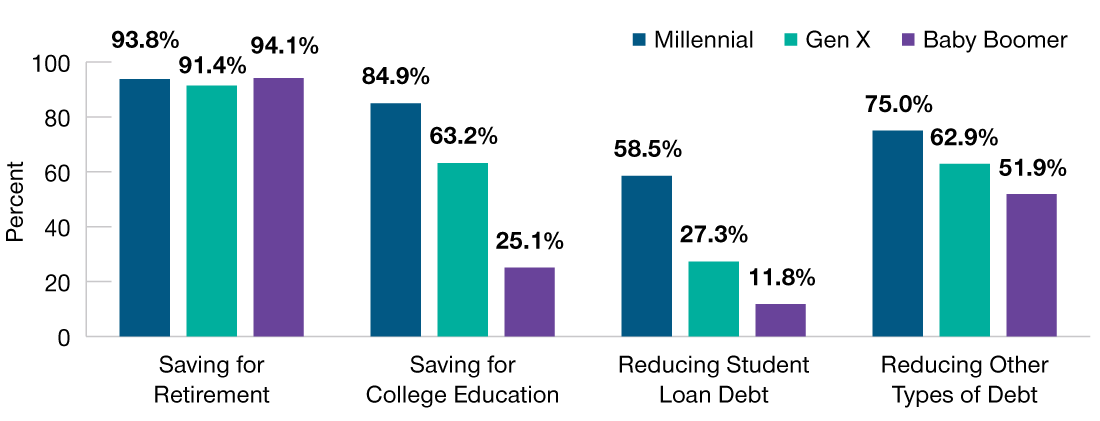

Individuals must set priorities before choosing how to spend their money. In T. Rowe Price’s 2019 Retirement Savings and Spending Study, retirement savers were asked about their varying financial priorities. The frequency of saving for college and repayment of student loan debt weighed heavily, but its relative importance changed with age.

Though the priority of saving for college and repayment of student loan (Fig. 5) debt declined in importance for Gen Xers, it remained significant. Also, given the higher levels of debt that millennials have had to assume, its level of prioritization may not decline as much as millennials progress to the lifestage now occupied by Gen Xers.

Plan Participation and Savings Rates Increased With Age

(Fig. 4) Yet, given a choice, many would choose not to save.

Source: T. Rowe Price Retirement Plan Services, year‑end 2019.

A Generational Look at Educational Debt

(Fig. 5) Millennials and Gen Xers were likely to say they have student loan debt.

Source: T. Rowe Price Student Loan Survey, December 2019.

Lastly and importantly, both the expense and the prioritization of funding postsecondary education as a goal does not seem to diminish until one is on the cusp of retirement—a reality that Gen Xers are facing today. The implication is that there are financial trade‑offs and decisions to be made between savings goals and debt management that are not defined by generational characteristics but rather by progression through lifestages. In short, both the goal of funding postsecondary education and the challenge to do so is likely to be increasingly persistent.

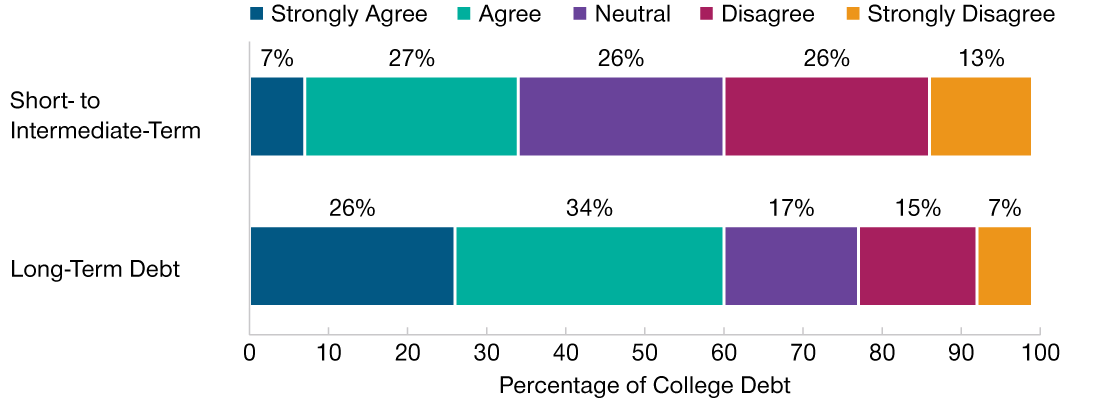

The last factor we identified as a contributor to the persistence of this problem is the perceived duration of debt. This is critical because it informs how those with debt may be mentally accounting for both how long it will take to repay it and how it becomes prioritized (or deprioritized) among life’s other expenses. Accordingly, we asked people how they viewed taking on student loans. What we found were conflicting attitudes.

Typically, college loan repayment is amortized over 10 years. However, that is not how it is perceived by the borrowers we surveyed. Only 34% shared the view (“strongly agree” or “agree”) that student loan debt is a short‑ or intermediate‑term debt, like auto loans or credit card debt (Fig. 6).

Number of survey respondents who believed that student loan debt is a long‑term debt, like a mortgage.

Instead, a majority (60%) viewed it more like a mortgage with a 30‑year term. Further, the belief that student loan debt is not a short‑ or intermediate‑term debt, like auto loans or credit card debt, was more widely held by those under 38 years old as of the study date (aka millennials). Thus, one can see the potential for these expenses to continue to be a factor well into midlife: the prime savings years for retirement.

Perception of Student Loan Debt

(Fig. 6) Many viewed it more like long‑term debt rather than intermediate‑term debt.

Source: T. Rowe Price Student Loan Survey, December 2019. Chart totals may not add to 100% due to rounding.

Debt Prevents Employees From Saving More for Retirement

The cost of funding one’s retirement is large in absolute terms. However, the cost to do so is relatively manageable in real terms because those who start saving early have approximately 45 years to benefit from years of accumulated savings and compounded returns. When it comes to saving for retirement, slow and steady typically wins the race.

Repaying student loans or saving for future educational expenses is fundamentally different. One has approximately 22 years to save for college (or, more broadly, postsecondary education), yet the debt is supposed to be repaid over 10 years.

The challenge for many is that these expenses coincide with the optimal time to start saving for retirement. Those who postpone retirement saving in order to pay off student loan debt, or for any other reason, do so at their peril. A dollar saved at age 50 doesn’t have the opportunity to compound as much as a dollar saved earlier in life.

Of course, there is a rational response to all of this, but savers do not always act rationally or even in their own best interests. Given that, one might wonder if an employer can benefit from their employees making better personal financial decisions or have an obligation to help them do so.

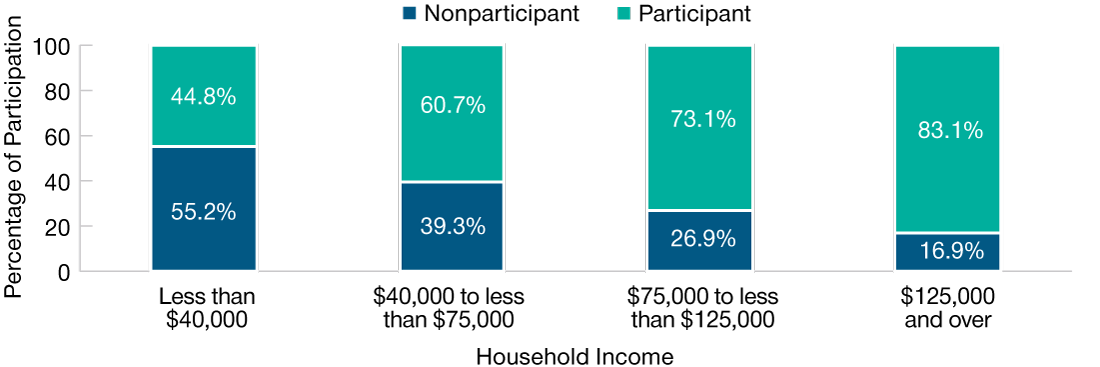

If there is an original sin to be found here, it is that retirement plan participation was correlated to household income (Fig. 7). Further, we also found that employees with student loan debt were less likely to participate in their employer’s 401(k) plan than those without the debt. Overall, 28% of those we surveyed had student loan debt and participated in their employer’s retirement plan. In contrast, 35% of nonparticipants said they had student loan debt.

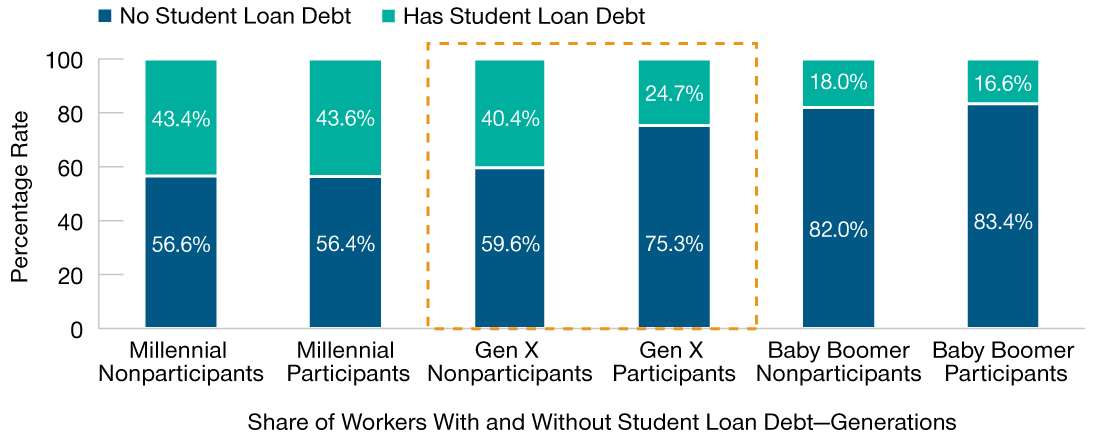

Though those that have student loan debt were less likely to participate in their employers’ retirement plan, simply looking at it through the lens of generational differences yields a significant curveball. Student loan debt affects generations differently.

Plan participation among millennials and baby boomers with and without student loan debt was similar. Where it differed significantly was among Gen Xers. Gen X had a statistically significant 15%‑point difference in plan participation between those who have student loan debt and those that do not (Fig. 8). This is potentially the result of a combination of repaying debt and the costs associated with paying for and/or saving for postsecondary education, suggesting that the drivers are likely not relating to generational characteristics, but are rooted in the increased financial complexity of these workers’ lifestage.

How Household Income Affected Plan Participation

(Fig. 7) More than half of workers making less than $40,000 did not participate in workplace savings plans.

Source: T. Rowe Price Student Loan Survey, December 2019.

It is not uncommon for those entering the workforce to have student loan debt just as it is very likely for those on the verge of retirement to have shed it. For Gen X, the additional burden of residual student loan debt presents a real barrier to retirement savings when coupled with the other types of financial obligations common at midlife. This may also serve as a cautionary warning about the prospects of millennials as they are at the cusp of midlife and will soon face similar challenges.

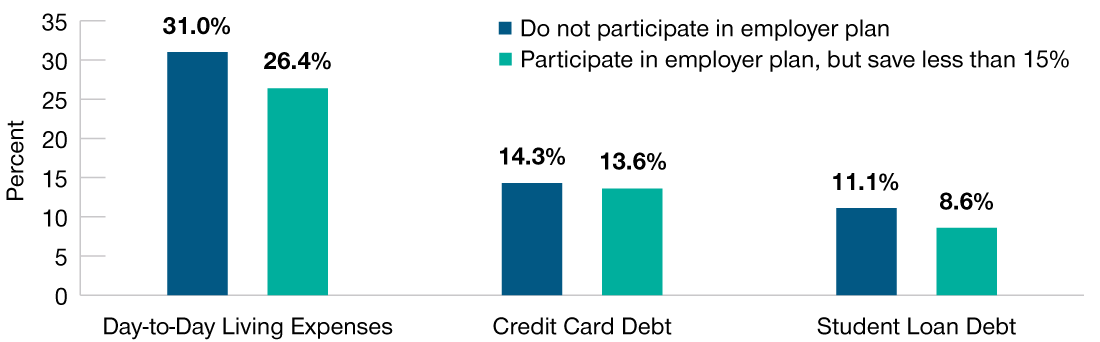

Student Loan Debt Is One of Many Barriers to Retirement Saving

Student loan debt is not the only barrier to retirement savings many workers face, but its specter seemingly looms large. Among those we surveyed, only 11% of the nonparticipants and 9% of those who were saving less than 15% of their wages6 cited student loan debt as a barrier to retirement savings. Instead, workers were more likely to cite both day‑to‑day living expenses (31% of nonparticipants and 26% of participants, respectively) and credit card debt (around 14% for both nonparticipants and participants, respectively) as greater barriers to retirement savings (Fig. 9).

"Coupled with what we know about wages and plan participation, there is an underlying current of financial fragility that prevents saving."

The findings suggest that both savers and non‑savers alike face basic financial well‑being challenges of balancing budgets and managing debts. Coupled with what we know about wages and plan participation, there is an underlying current of financial fragility that prevents saving.

Despite these concerns, almost two‑thirds of those we surveyed still felt that investing in education was a good investment, even if it meant taking on loans to pay for it. However, the decision to take on this debt and its longer‑term implications are often not fully considered. In fact, almost half of those we surveyed now admit they “did not think about the costs of student loans when they first took them, but it is a great concern.” This figure rose to 63% for those that did not ultimately receive their degrees. It gets worse. More than half (52%) of those we surveyed “strongly agree” or “agree” that postsecondary education expense is a barrier to achieving other financial goals.

The pattern is troubling. Workers are taking on larger and larger sums of debt to pay for education. Even though they think the debt is a good investment, repayment is challenging given other expenses. As a result, long‑term wealth accumulation through retirement savings and home ownership is given a lower priority than day‑to‑day living expenses and managing debt. Not surprisingly, 78% of those who were repaying college loans and 72% who were saving for future or paying current postsecondary educational expenses felt (“strongly agree” or “agree”) this kind of debt was overwhelming, regardless of the amount.

Gen Xers With Student Loan Debt May Struggle to Save for Retirement

(Fig. 8) Baby boomers and millennials with student loan debt were equally likely to save for retirement as those without student loan debt.

Source: T. Rowe Price Student Loan Survey, December 2019.

Daily Living Expenses Were the Most Common Barrier to Saving for Retirement

(Fig. 9) Among those who don’t participate or save 15%.

Source: T. Rowe Price Student Loan Survey, December 2019.

What the data tell us is that student loan debt occupies a special place in a debtor’s psyche. Workers often make hasty or ill‑considered decisions relative to the size of the debts and expenses they take on and often make poor tradeoffs which are counterproductive to reaching common financial goals. A profound example of this can be found in analyzing Department of Education statistics on the portfolio performance of Direct Student Loans. Our analysis revealed that 35% of the borrowers who were at least 31 days delinquent owed less than $10,000.7 In short, there is a lot of behavior that suggests that how people address paying off student debt or saving or paying for postsecondary education may not be entirely rational.

Still, there is some good news. Those affected by student loan debt or the costs associated with postsecondary education can always save more for retirement in the future; but it is very difficult, and they would be better served by making better choices today.

The cost of higher education is significant and has fundamentally changed how we order our financial lives. Figures from Educationaldata.org suggest that the average total cost, using 2019–2020 academic year expenses, for four years of education, including tuition, room and board, books, and other expenses will cost an in-state student an estimated $101,984 at public institution and $212,868 at a private institution; well beyond the means of most families.8

Among those who responded to our survey and had student loan debt, the median unpaid balance was above $30,000.9 Still, almost 8/10 surveyed stated their intention to save more in the future, consistent with the behavior we generally observe among recordkept participants as they age.

The challenge for all is to ensure that those dealing with the costs of postsecondary education who are also saving for retirement do so in a manner that optimizes the outcomes for both rather than sacrificing one for the other.

Financial Priorities of Savers

(Fig. 10) Retirement, education, and reducing debt outranked student loan debt.

Source: 2019 T. Rowe Price Retirement Savings and Spending Study.

When people join the workforce, they must make decisions about how they spend their money. As a practical matter, there is no difference between saving and consumption: A dollar saved is simply a dollar of deferred consumption. Still, the absolute number of dollars available to consume is finite, and savers, regardless of age, must make choices between what they save for and for which debts they prioritize repayment. Further, our 2019 Retirement and Savings and Spending Study findings showed that retirement is an important financial goal, but so were funding or repaying educational expenses and managing debt. (Fig. 10).

Our research has shown that costs associated with postsecondary education have fundamentally changed financial priorities for millions of workers. In our survey of 2,400 retirement plan participants, we found that more than half of those who responded (54%) were either repaying student loans or saving for future or paying postsecondary educational expenses. Though millennials are most affected in terms of student loan debt, Gen Xers are also significantly affected due to lingering debts and current or future expenses. This is a harbinger of what is to come for millennials as they age.

Considerations for Employers

At the outset of this paper, we suggested that there are two crises facing many workers—retirement savings shortfall and student loan debt. Further, we implied that the two crises are not unrelated. In fact, a regression analysis revealed that people who have student loan debt are less likely to participate in their employer’s retirement plan than those who do not have the debt. Our research also suggests that the challenges created by student loan debt may be exacerbated with time as millennials progress into midlife and as Gen Xers move toward retirement.

Some employers have chosen to address this challenge head on with custom plan designs and benefit programs that help employees address student loan debt or achieve greater financial wellness. There are also several public policy ideas, proposed legislation, and forms of regulatory relief under consideration that could also benefit both employers and workers who are affected by student loan debt. Accordingly, both employers and their service providers need to be mindful of these potential developments.

In order to properly define workers’ financial challenges, one must consider what roles debt management and savings goals play over the course of a person’s working lifetime. Let’s assume that someone is entering the workforce at age 22 and expects to retire at age 67. As different savings goals and debt repayments emerge over the course of 45 years, individuals may have to prioritize some or all of these significant goals.10 Moreover, these priorities change over time.

"Our research demonstrates that people often need assistance properly prioritizing financial goals and developing healthy financial behaviors."

Our research demonstrates that people often need assistance properly prioritizing financial goals and developing healthy financial behaviors. That said, employers are not bystanders to the financial challenges their employees face. There is a growing recognition of an interconnectedness between the workplace and employees’ financial well‑being. Moreover, employers have an increasing number of technologies and service offers available to them to address this trend that simply did not previously exist. The decision employers now face, if they choose to go down this path, is what role do they wish to assume, what strategies do they wish to employ, and how will they seek to implement them.

In T. Rowe Price’s 2019 Retirement Savings and Spending Study, 62% of 401(k) plan participants said they were relying on the company that manages the 401(k) account to help them achieve their lifetime financial goals. Given the damaging effects of financial stress, such as lost productivity, absenteeism, mental health issues, etc., employers would do well to adopt programs that directly address the root causes of financial hardship and provide programmatic remedies to serve their and their employees’ long‑term best interests. Given workers’ existing relationship and affinity with their 401(k) recordkeeper, these companies are uniquely positioned to help both employers and employees.

Hypothetical Lifestage Financial Goals

Ways that employers can help their employees become more adept at managing day‑to‑day expenses, managing debt such as student loans, and saving for both short‑ and long‑term financial goals, such as emergency and retirement savings, include offering:

- Plan design features (e.g., auto‑enrollment, auto‑escalation, matching formulas, vesting, employer contributions, etc.) that both nudge and incentivize plan participation and savings among the employee populations least likely to do so.

- Programs that help employees assess their point‑in‑time financial health; set, monitor, and prioritize meaningful financial goals; and create personalized actions that can improve one’s financial well‑being.

- Educational programs and tools that help employees budget their monthly living expenses to align the income with both debt management and savings goals (e.g., emergency savings, retirement, home purchase, etc.).

- Programs (e.g., counseling, repayment assistances, financing, etc.) that help savers manage not only student loan and other types of debt repayment, but also help savers prepare for future educational expenses (as evidenced by the needs of Gen Xers) that are proving to be barriers to retirement savings and overall financial well‑being.

- Modeling tools that allow employees to consider the trade‑offs in making financial decisions, such as taking on debt for postsecondary education; making large expenditures, such as housing or automobiles; or allocating resources toward savings goals or toward paying down debt.

- Access to multiple modes of engagement that span from digital to in‑person so that those who seek counseling or coaching can do so in a manner that best meets their needs.

Sadly, for those who are struggling to meet the demands of repaying student loan debt and saving for retirement, it is not a tempest in a teapot. Rather, it is indicative of the struggle many have in balancing day‑to‑day expenses, managing debt, and saving for both long‑ and short‑term financial goals. It is our hope that this research has both shed light and given perspective on the dimensions of the challenge workers face and how employers can help their employees meet and overcome these challenges and thrive financially.

T. Rowe Price fielded an online survey of over 2,400 workers employed by its retirement services recordkeeping clients. All the respondents were eligible for their employer’s 401(k) plan, although not all participated. Those who are repaying student loan debt or saving for future or paying current postsecondary educational expenses were asked a series of questions about student loans and their perceptions around postsecondary educational expenses and retirement savings. Those not impacted by these expenses were only asked for basic demographic data for comparative purposes. The survey was fielded in December 2019, and T. Rowe Price was identified as the sponsor of the research.

The Retirement Saving and Spending Study was conducted by NMG Consulting and included a sample of 3,016 retirement plan participants, 250 eligible non-plan participants, and 603 individuals without access to workplace savings plans. The survey was conducted online from June 13–25, 2019.

This paper was originally published in August 2020 and is being provided for informational purposes only.

Find this article interesting?

Subscribe to get email updates including article recommendations relating to retirement.

-

1 VanDerhei, Jack, Ph.D., “Retirement Savings Shortfalls: Evidence From EBRI’s 2019 Retirement Security Projection Model®,” ebri.org Issue Brief, March 7, 2019, No. 475, p.11.

2 T. Rowe Price analysis of Federal Student Loan Portfolio (inclusive of Direct, Federal Family Education Loans, and Perkins Loans).

3 2016 Survey of Consumer Finances, https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/scfindex.htm, table 3.

4 Trends in College Pricing 2019, College Board, p.13.

5 © 2018, Matthew S. Rutledge, Geoffrey T. Sanzenbacher, and Francis M. Vitagliano. All rights reserved.

6 Investment Professionals at T. Rowe Price suggest that individuals save, through a combination of employee and employer contributions, 15% of one’s wages.

7 U.S. Department of Education, Direct Loan Portfolio by Delinquency Status and Debt Size, Enterprise Data Warehouse, 4Q2019.

8 Educationdata.org, The Average Cost of College & Tuition, https://educationdata.org/average‑cost‑of‑college/

9 Depending on qualification (e.g., dependent or independent), undergraduates can borrow up to $12,500 per year in direct subsidized and unsubsidized loans. The figure rises to $20,500 in unsubsidized loans for graduate school.

10 Hypothetical timeline of debt repayment and savings goals.

-

Important Information

This material is provided for general and educational purposes only and not intended to provide legal, tax, or investment advice. This material does not provide recommendations concerning investments, investment strategies, or account types; it is not individualized to the needs of any specific investor and not intended to suggest any particular investment action is appropriate for you, nor is it intended to serve as the primary basis for investment decision-making.

The views contained herein are those of the authors as of August 2022 and are subject to change without notice; these views may differ from those of other T. Rowe Price associates.

This information is not intended to reflect a current or past recommendation concerning investments, investment strategies, or account types, advice of any kind, or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any securities or investment services. The opinions and commentary provided do not take into account the investment objectives or financial situation of any particular investor or class of investor. Please consider your own circumstances before making an investment decision.

Information contained herein is based upon sources we consider to be reliable; we do not, however, guarantee its accuracy.

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. All investments are subject to market risk, including the possible loss of principal. There is no assurance that any investment objective will be achieved. All charts and tables are shown for illustrative purposes only.

T. Rowe Price Investment Services, Inc., Distributor.

© 2022 T. Rowe Price. All rights reserved. T. Rowe Price, INVEST WITH CONFIDENCE, and the Bighorn Sheep design are, collectively and/or apart, trademarks of T. Rowe Price Group, Inc.