August 2021 / MARKETS & ECONOMY

How Digital Currencies Add Policy Potency for Emerging Markets

More monetary policy control as rate decisions have a broader impact

Key Insights

- By increasing financial inclusion, digital currencies have the potential to be transformative for emerging market (EM) monetary policies, broadening the impact of rate changes.

- A potential outcome is lower inflation and interest rate volatility and, ultimately, lower long‑term bond yields.

- Over time, central bank digital currencies could help EM monetary policy move toward developed market levels of monetary policy efficacy.

Digital currencies issued by emerging market (EM) central banks are set to enhance financial inclusion and facilitate greater control over their nations’ economies. As central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) are adopted in EM countries, more people become directly exposed to interest rate decisions, greatly strengthening the power of monetary policy. This will likely reduce inflation and interest rate volatility and, ultimately, lower long‑term bond yields.

In this third article in a series, we discuss how CBDCs will strengthen monetary policy in EM countries and how changes in the savings and investment balances will strengthen the economies of those countries.

Deeper Financial Inclusion Makes Interest Rates a More Powerful Tool

CBDCs have significant potential to increase the number of people participating in the financial system, particularly in EM countries. Indeed, a Bank of International Settlements survey (December 2020) showed that financial inclusion is the most important motivation for EM central banks to explore digital currencies.

Currently, a significant proportion of populations in EM economies lack access to bank accounts, so they have no direct exposure to interest rate movements. This means that monetary policy affects a large proportion of the population only through indirect channels, such as output, inflation, and the exchange rate. These variables affect the behavior of every citizen in the economy, irrespective of their level of participation in the financial system.

However, many EM countries prefer to keep currency fluctuation within a band pegged to the currencies of their major trading partners to maintain external competitiveness. This “fear of floating” leaves output and inflation as the main avenues through which most citizens are affected by monetary policy. Although the effect on output from monetary policy changes helps employment, the consequences of inflation are felt most by those outside the financial system, particularly those who do not have an easy way to protect the value of their savings (such as access to an interest rate‑bearing savings account).

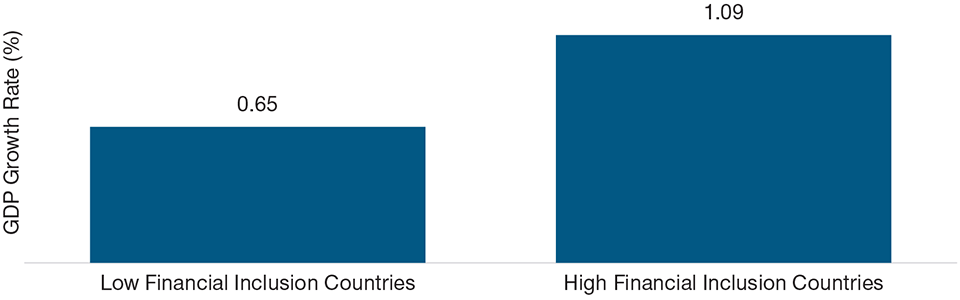

By contrast, developed market (DM) policy rates influence a significant proportion of the population through interest rates on savings accounts, financial instruments, and loans. This difference between developed and emerging markets is the key reason why monetary policy in the former is more effective at stabilizing the business cycle and inflation: As changes in interest rates affect all citizens, the direct economic consequences of monetary policy are quantitatively much larger. Indeed, our own estimation shows that the effect of monetary policy on output is two‑thirds more powerful in a country with high financial inclusion relative to one with low financial inclusion.

How CBDCs Work to Influence Spending and Saving Behaviors

EM CBDCs that are already in circulation, such as the Bahamian sand dollar, allow individuals to access banking services without the need to provide an address or proof of formal income. The ease of opening CBDC accounts and the ability to save directly exposes many more individuals to the interest rate decisions of the central bank.

People without bank accounts often end up spending a large proportion of their income because they have nowhere to save or protect income from inflation. However, interest rates on CBDC accounts may influence account holders’ spending decisions—potentially encouraging them to delay or bring forward consumption or investment. With this greater influence on the spending decisions of individuals and businesses, central banks will be able to mitigate business cycle shocks and reduce economic volatility more effectively as they strive to achieve monetary policy targets.

The use of digital currencies will also allow individuals and businesses to build a verifiable history of income and spending in a CBDC, which can help support loan applications. Greater access to credit will reduce the reliance on shadow banks and increase the reliance on regulated financial intermediaries, which are likely to offer interest rate products linked to the central bank policy rate.

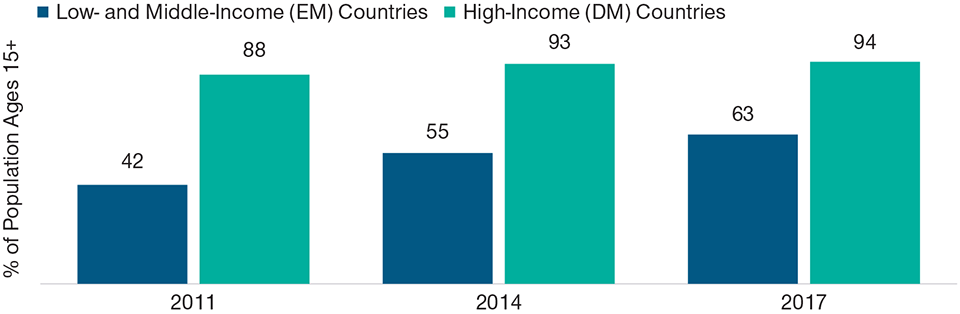

In low- and middle‑income EM countries, this technology could increase the proportion of the population participating in the financial system from around 60% to 90%. This, in turn, would make monetary policy in these countries significantly more effective and would reduce the equilibrium interest rate. It will also mean that changes in the interest rate are more powerful, therefore reducing the volatility of interest rates.

Much Smaller Proportion of EM Populations Hold Bank Accounts

(Fig. 1) While steadily narrowing, the gap between EMs and DMs has historically been large

As of December 2017 (most recent data available).

Source: World Bank.

CBDCs May Reduce the Gap Between EM and DM

Over time, CBDCs could help EM monetary policy attain levels of monetary policy effectiveness more akin to DMs. A Bank of International Settlements report1 states that greater financial inclusion will lead to a fall in output and inflation volatility due to a rise in intertemporal substitution, financial market development, and reduced sensitivity to some types of shocks (such as natural disasters). For countries with inflation‑targeting central banks, inflation volatility is likely to fall more than output volatility as greater emphasis is given to stabilizing inflation relative to output.

Greater access to bank accounts will increase the level of individual domestic savings available for investment in the economy, which would make current account deficit‑running EM countries less dependent on foreign capital. Although the initial impact is likely to be negligible, the effect will grow over time as more individuals gain access to banking services and savings are built. In the long term, the lower reliance on external finance will mean that the central bank is less likely to respond to external conditions such as hiking the policy rate in response to a hike in the US Federal Reserve’s policy rate (in order to maintain the interest rate differential and attract capital inflows). Monetary policy will become more dependent on local economic conditions rather than external conditions, which will help the central bank achieve its target and improve financial stability.

Issuing CBDCs will also have implications for the structure and size of the EM central bank balance sheet. CBDCs will act as a liability on the balance sheet and there must, therefore, be an asset on the counterpart. In DM countries, the natural asset is government debt given its risk‑free properties. However, in many EM countries, government debt is not considered risk‑free and may have a low credit rating, in which case individuals may not be willing to hold CBDCs backed by local government debt. A possible solution to this would be for EM central banks to issue CBDCs against DM government debt, therefore reducing the inherent riskiness of CBDCs and encouraging their use. Indeed, many EM central banks already accumulate reserves when they lean against appreciating pressure on their currencies.

Interest Rate Impact on Growth Varies With Levels of Financial Inclusion

(Fig. 2) Rise in real GDP in response to hypothetical 100 basis points short‑term rate cut

As of December 2020.

For illustrative purposes only.

Sources: World Bank, Willems (2020), and T. Rowe Price calculations.

Implications for Currency and Bond Investors

As monetary policy becomes a more powerful tool in managing the economy in EMs, the equilibrium interest rate will fall. Furthermore, the lower volatility of output and inflation will lead to a fall in the volatility of interest rates, therefore reducing the term premium and lowering the level of long‑term bond yields.

The impact on currencies will be mixed. Although a lower equilibrium interest rate indicates a weaker currency, the larger pool of domestic savings will reduce the reliance on external financing and suggests a stronger currency. An increase in domestic savings will also be supportive for bond yields. The net impact will vary by country and will depend on the current level of financial inclusion, the effectiveness of monetary policy, and the speed at which CBDCs are implemented. The difference in impact will also create relative value opportunities for investors.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

This material is being furnished for general informational and/or marketing purposes only. The material does not constitute or undertake to give advice of any nature, including fiduciary investment advice, nor is it intended to serve as the primary basis for an investment decision. Prospective investors are recommended to seek independent legal, financial and tax advice before making any investment decision. T. Rowe Price group of companies including T. Rowe Price Associates, Inc. and/or its affiliates receive revenue from T. Rowe Price investment products and services. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. The value of an investment and any income from it can go down as well as up. Investors may get back less than the amount invested.

The material does not constitute a distribution, an offer, an invitation, a personal or general recommendation or solicitation to sell or buy any securities in any jurisdiction or to conduct any particular investment activity. The material has not been reviewed by any regulatory authority in any jurisdiction.

Information and opinions presented have been obtained or derived from sources believed to be reliable and current; however, we cannot guarantee the sources' accuracy or completeness. There is no guarantee that any forecasts made will come to pass. The views contained herein are as of the date noted on the material and are subject to change without notice; these views may differ from those of other T. Rowe Price group companies and/or associates. Under no circumstances should the material, in whole or in part, be copied or redistributed without consent from T. Rowe Price.

The material is not intended for use by persons in jurisdictions which prohibit or restrict the distribution of the material and in certain countries the material is provided upon specific request.

It is not intended for distribution retail investors in any jurisdiction.

August 2021 / MARKETS & ECONOMY