June 2022 / INVESTMENT INSIGHTS

Why We Have Become More Favourable on Duration

Key indicators suggest that yields have peaked

Key Insights

- After adopting underweight duration positions last year, many of our fixed income strategies have begun to add duration back to their portfolios.

- Key growth, inflation, and monetary policy indicators all suggest that yields may have peaked and could even come down.

- Also supportive are the resumption of the negative correlation between stocks and bonds, the stable U.S. Treasury yield, and the fall in interest rate volatility.

After adopting underweight duration positions across our investment platforms in the second half of last year, many of our fixed income strategies are adding back duration to neutral or long positions. The reason is simple: We believe that U.S. Treasury yields have likely peaked for the medium term and that now is therefore a good time to own duration. We have several reasons for believing this, which we explore further below.

Forecasting yields is simple, but never easy. Our simple approach focuses on three main fundamental drivers of yields: growth, inflation, and monetary policy. When examining each of these, we pay much more attention to the underlying rate of change than to the level at a given moment in time.

Three Key Indicators Suggest a Peak Has Been Reached

Take growth: We believe the near‑term outlook for U.S. growth is negative because of the looming prospect of reduced fiscal spending, tighter financial conditions (as seen in sharply higher U.S. mortgage rates, a stronger U.S. dollar, and a weak equity market), and declining purchasing power due to high inflation. All these factors will negatively impact growth over the rest of this year. Indeed, the National Association for Business Economics has already cut its 2022 U.S. growth forecast to 1.8% compared with a median forecast of 2.9% in February, and, more importantly, recent data have begun to disappoint these already lowered expectations. Offsetting these growth headwinds is the very low U.S. unemployment rate, which will likely be enough to persuade the Federal Reserve to continue its hiking path.

Forecasting Inflation Has Been a Fool’s Errand

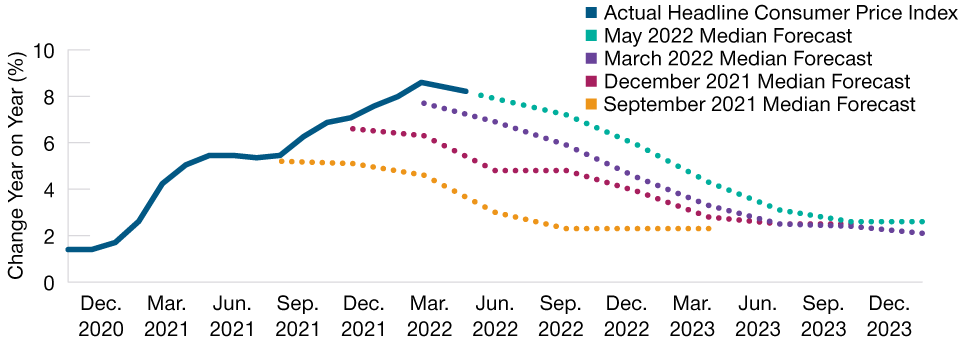

(Fig. 1) Consumer prices have risen much more than expected

As of April 30, 2022.

There is no guarantee that any forecasts made will come to pass.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P.

The second area we look at is inflation. Predicting inflation has been virtually impossible over the past 18 months—the inaccuracy of some predictions has reached almost comical proportions (Figure 1). This has finally begun to change, though: Inflation expectations have stopped moving higher, and when the data have come in, they have mostly met those expectations.

This is a significant development. It tells us that we have probably reached a peak in U.S. inflation and, therefore, a peak in yields. It is an elevated peak, certainly, but—as mentioned above—we are more interested in the rate of change than the level. It is not difficult to see how we got here: Inflation volatility finally prompted the Fed to start earnestly playing catch‑up last September, then this monetary policy volatility led to interest rate volatility, higher yields, and general market volatility. Now it looks like the tide is beginning to turn.

This is also evident in our third area of focus, monetary policy. Although the Fed is expected to continue tightening until next year, in the press conference following its last policy meeting, Chair Jerome Powell flatly rejected a 75 bps hike, opting instead for a 50 bps rise. The pushback against a 75 bps hike, which would have been the most aggressive single policy tightening since 1994, suggests that while the Fed remains hawkish, its hawkishness has ceased to accelerate. And if we have reached a peak in monetary policy hawkishness at the same time that inflation is peaking and growth is slowing, then it is reasonable to say that “Act 1” of the current phase in financial markets has ended—and that it is consequently a better time to own duration (Figure 2).

“Act 1” of the Current Phase in Markets Has Likely Ended

(Fig. 2) The three fundamental drivers point to lower yields

Source: T. Rowe Price.

Other Data Points Are Supportive

In addition to the three areas described above, other data points support our view that yields may have peaked and that the aforementioned fundamental drivers will take precedence. The first is the stock/bond correlation. For much of this year, stocks sold off at the same time as bond yields rose—in other words, they were positively correlated. This is not a welcome occurrence because it means that stocks and bonds are not hedging each other in the way they have historically. Recently, however, the traditional negative correlation between stocks and bonds has resumed—yields have fallen in tandem with equity markets, meaning that bonds appear to have once again become an effective hedge for stocks. This may prove useful in the period ahead as the Fed is unlikely to pause its hiking cycle in response to any equity market declines—as it has done in the past—given its strong focus on inflation.

Another encouraging sign is that the benchmark 10‑year U.S. Treasury yield seems to have stabilized. It rose above 3% in early May for the first time since December 2018 and has since fallen to just below 3%, indicating that there is strong demand at around the 3% level and that investors have covered their prevalent short duration positions. At the same time, interest rate volatility has also begun to decline slightly, which is important not only for adding duration but also for market risk in general.

Overall, then, it seems that the links in the chain that caused yields to rise so dramatically—inflation volatility, monetary policy volatility, rate volatility, and market volatility—are beginning to weaken. It is not yet clear whether the pattern will go into reverse, but in many areas we appear to have reached the point at which things have stopped getting worse. Yields are therefore likely to at least stabilize and may even decline if recession risk rises. The curve‑flattening trend that typically occurs during Fed tightening cycles is also likely to resume.

Looking to the Next Phase

The biggest risk to our more positive view on duration is inflation. If inflation continues to surprise on the upside, our belief that now is a good time to add duration will be proved wrong. Here again, however, the data seem to support our view. The differentials between Treasury inflation protected securities (TIPS) and nominal Treasuries of a similar maturity (the market‑based indicator of inflation expectations) stopped moving higher a few months ago and has begun to move lower. In a further sign of declining inflationary pressures, commodity prices—a leading indicator of inflation—have begun to fall.

As things stand, we expect the Fed to hike by 50 bps in its June and July meetings, then by 25–50 bps in September and 25 bps in every subsequent meeting until March next year. This would take the fed funds rate to above 3% by early 2023, considerably above the Fed’s forecast “neutral” rate (the estimated level at which an economy is neither overheating nor slowing) of around 2.4%.

At that point, we believe growth will either stabilize or there will be a recession. The chances of the latter have increased because the Fed is hiking while growth is slowing, although it is difficult to envisage a severe recession while the labor market remains as strong as it is now. In either case—a soft landing or a mild recession—it looks as if the phase of rising yields and elevated rate volatility is over and the next phase in the cycle is about to begin, which is why many of our strategies have been adding duration back to their portfolios.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

This material is being furnished for general informational and/or marketing purposes only. The material does not constitute or undertake to give advice of any nature, including fiduciary investment advice, nor is it intended to serve as the primary basis for an investment decision. Prospective investors are recommended to seek independent legal, financial and tax advice before making any investment decision. T. Rowe Price group of companies including T. Rowe Price Associates, Inc. and/or its affiliates receive revenue from T. Rowe Price investment products and services. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. The value of an investment and any income from it can go down as well as up. Investors may get back less than the amount invested.

The material does not constitute a distribution, an offer, an invitation, a personal or general recommendation or solicitation to sell or buy any securities in any jurisdiction or to conduct any particular investment activity. The material has not been reviewed by any regulatory authority in any jurisdiction.

Information and opinions presented have been obtained or derived from sources believed to be reliable and current; however, we cannot guarantee the sources' accuracy or completeness. There is no guarantee that any forecasts made will come to pass. The views contained herein are as of the date noted on the material and are subject to change without notice; these views may differ from those of other T. Rowe Price group companies and/or associates. Under no circumstances should the material, in whole or in part, be copied or redistributed without consent from T. Rowe Price.

The material is not intended for use by persons in jurisdictions which prohibit or restrict the distribution of the material and in certain countries the material is provided upon specific request.

It is not intended for distribution to retail investors in any jurisdiction.