January 2021 / INVESTMENT INSIGHTS

UK Investors Should Prepare for Negative Interest Rates

The role of gilts in portfolios could be impacted

Key Insights

- Implied policy rates show that the markets do not expect the Bank of England to adopt negative rates as a policy tool.

- We believe the markets are wrong, however, and that UK investors need to prepare for negative interest rates.

- The Bank of England is already consulting with financial institutions about practical, legal and operational implementation.

Negative interest rates are likely coming to the UK, but you would not know that judging from the markets. Although rates are widely expected to fall, implied policy rates show that the markets do not expect the Bank of England (BoE) to adopt negative rates as a policy tool over the next few years. We believe the markets are wrong, however, and that UK investors need to prepare for the prospect of negative interest rates.

The coronavirus has hit the UK economy hard: Once the effects of the second lockdown are factored in, economic growth is on course for the largest annual decline since the Great Frost of 1709. The transition to any new trade agreement with the EU will be disruptive, particularly in the early part of 2021. The UK government has acted to support the economy, but at the cost of a 20% budget deficit—an all‑time high in peacetime.

Historically, UK governments have begun to consolidate large deficits soon after the event. Indeed, the UK Office of Budget Responsibility is predicting a structural tightening of 11.5% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2021–2022. These substantial headwinds will require monetary policy to continue supporting the recovery for a long time, even after a mass COVID‑19 vaccination programme has been completed.

Why Negative Rates Are on the Horizon

Four key reasons

Why Might the Bank of England Resort to Negative Rates?

The economic slowdown caused by the pandemic has substantially increased the amount of spare capacity in the UK economy. This spare capacity, known as the output gap, is currently 10% of GDP. Reducing output gaps is a key goal of economic policy—in response to the 6% gap that followed the 2008 global financial crisis, the BoE cut interest rates by 5.25%, bought GBP 375 billion of government debt via quantitative easing (QE) and made it easier for people to get credit via the Funding for Lending Scheme.

This time, the BoE has relied heavily on QE to support the economy and currently owns 44% of the eligible universe of gilt securities. While this is below its self‑imposed limit of 70%, by comparison, the Bank of Japan found that it had to resort to yield curve control when it reached ownership of close to 50% of Japanese government bonds as distortions started to appear in the market. The scope for further QE, therefore, appears to be limited.

In response to the coronavirus, the BoE introduced the Term Funded Scheme with additional incentives for SMEs (TFSME) to help ease bank credit conditions and thereby stimulate economic activity. However, recent months have shown increased rates for high loan‑to‑value retail mortgages, reflecting strong continued demand from borrowers and expectations of increased defaults in the near term. Given the desire to encourage prudent bank lending following the global financial crisis, additional intervention by the BoE to reduce these mortgage rates appears unlikely.

Which brings us to negative policy interest rates. The BoE is already consulting with financial institutions about practical, legal and operational (e.g., IT) implementation. Negative policy rates would be expected to reduce lending rates for business, consumers and the government and stimulate the economy through a lower value for sterling in foreign exchange markets. An important behavioural channel is that a negative policy rate, even if it is not passed on to them directly through negative interest rates on deposit accounts, will remind households to consume some of the large savings they accumulated during the lockdowns in 2020.

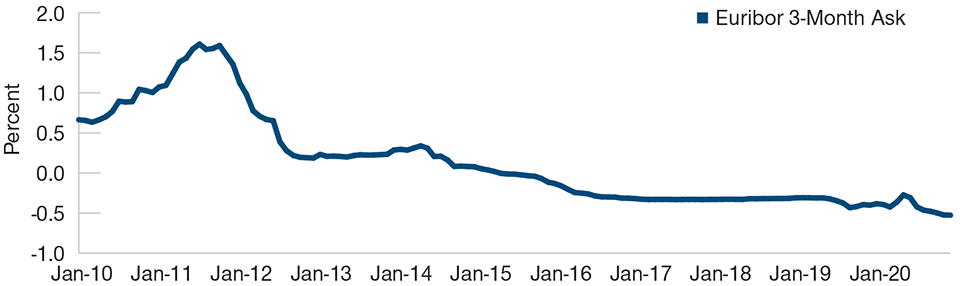

Negative Rates Are Not a New Phenomenon

(Fig. 1) Euribor has been below zero since 2015

For illustrative purposes only.

As of 30 November 2020.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P.

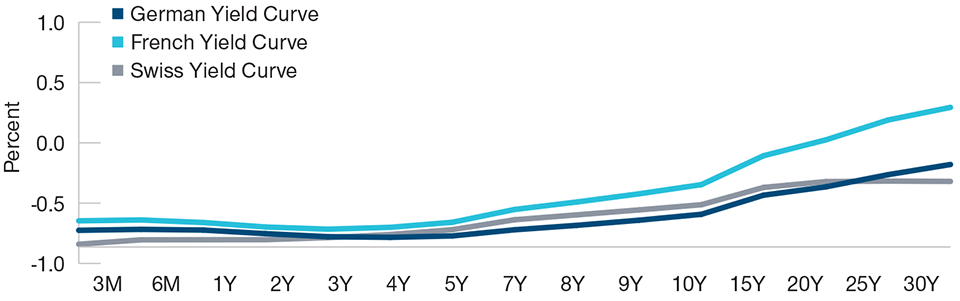

Zero Is Not a Lower Bound for Sovereign Yields

(Fig. 2) German, French and Swiss debt are in negative territory

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. For illustrative purposes only.

As of 30 November 2020.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P.

What Can We Expect? Look to Other Countries as a Guide

Negative policy interest rates were first deployed by Switzerland in the 1970s and have found favour again in recent years. Central banks in Denmark, Switzerland, Sweden, Japan and the eurozone have moved rates below zero to support economic recoveries or manage key exchange rates. The experiences of these countries have shown that such policies can help stimulate the economy through a combination of weaker exchange rates and cheaper debt.

Financial markets have generally reacted quickly to the new reality of negative rates without any problems. Measures of borrowing rates such as the Euro Interbank Offered Rate (Euribor), widely used in derivative contracts such as interest rate swaps, have now been below zero for years without creating issues in the functioning and valuation of such instruments.

Similarly, markets for government debt have reacted to the policy signals provided by central banks. Yields on government bonds from major issuers such as Germany are now negative at all maturities—showing that zero is not a lower bound for medium‑ and longer‑term yields.

Implementation—A Possible Pathway for Negative Rates

In the near term, the risk of further pandemic‑related restrictions and disruption from a transition to new trade arrangements with the EU may provide significant downside growth surprises in early 2021, which could prompt the BoE to implement this policy. However, an emerging consensus among central bankers is that it is best to implement negative interest rates when the financial system is not under stress. As the effects of transitioning to a new EU trade arrangement at year‑end on the UK’s financial system are unclear, the earliest implementation of negative rates would be mid‑2021.

The key potential upside for the economy in 2021 is a rapid rollout of an effective COVID‑19 vaccine. Even if a successful mass vaccination scheme leads to a rapid recovery, growth weakness from the pace of fiscal tightening and a slow global recovery means that we believe negative rates at some point in the coming years are a likely outcome.

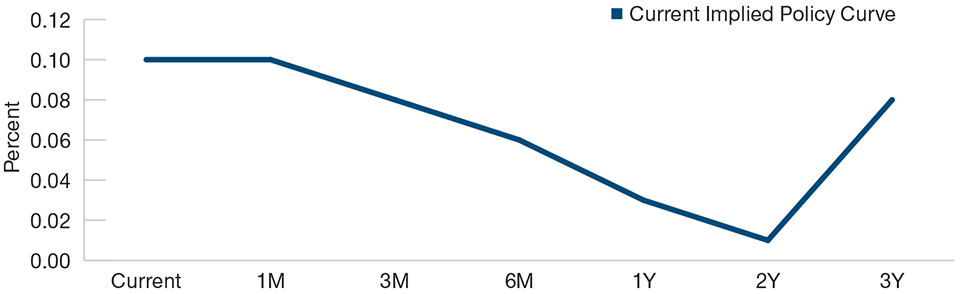

The Markets Do Not Expect Negative Rates in the UK

(Fig. 3) Implied policy rates still hover north of zero

Policy rates are implied based on overnight GBP reference rates. For illustrative purposes only.

As of 30 November 2020.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P.

The duration of a negative interest rate policy depends on the speed of economic improvement. For example, the European Central Bank entered its negative rate regime in 2014, but weak growth left rate rises looking unpalatable even before the current pandemic. But recent history shows the UK could be different: The policy mix UK authorities adopted from 2009 showed that monetary policy can mitigate tight fiscal policy and generate inflation back towards the BoE’s target of 2%. We believe that a recovering UK economy would allow an eventual exit from the policy, albeit after several years.

Why the Markets Are Not Pricing In Negative Policy Rates

At the time of writing, markets are not expecting negative policy interest rates for the next three years. Although policy rates are expected to fall over 2021 and 2022, the markets do not seem to expect the UK to adopt a negative interest rate policy. This is probably because moving into a negative rate regime is a major step and, given the myriad uncertainties around global growth, vaccination progress and Brexit disruption, it is difficult for markets to assess the probability of such a change with confidence. This means that markets will probably only react when there is more clarity on some of these key risks or when the BoE’s likely policy approach becomes clearer.

If the BoE moved short‑term interest rates into negative territory, it would likely extend the rally in medium‑ and long‑dated gilts. Experience shows that negative rates can be difficult to exit once implemented, indicating they could be around for a while. Furthermore, a negative rate on banks’ reserves at the BoE will lead to a search for yield to limit the impact on profits—hence greater demand for positive‑yielding gilts.

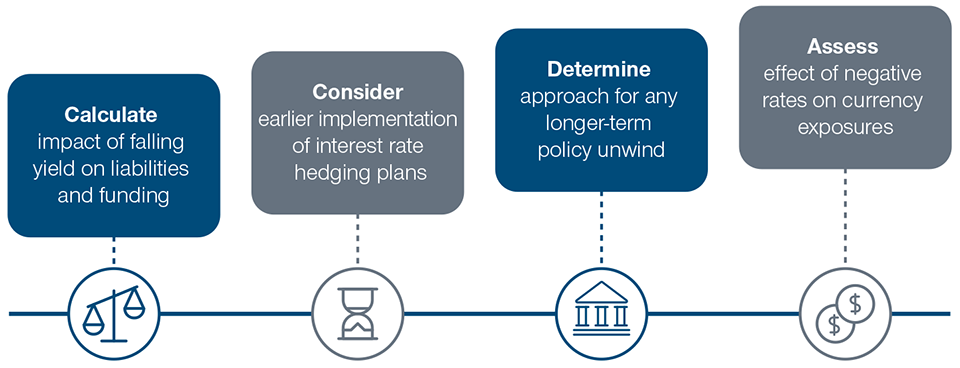

Next Steps for UK Investors

In foreign exchange markets, negative interest rates would reduce sterling’s current yield advantage over the euro in particular, likely resulting in the two currencies moving closer to parity. While lower rates of sterling have tended to boost UK equities given companies’ high level of overseas exposure, we believe that equity market sentiment is more likely to be driven by wider global developments and the pace of pandemic recovery.

Preparing for Negative Rates—Actions for UK Investors to Consider

We would not expect negative policy rates to disorder gilt, cash or derivative markets. A bigger concern for investors is whether the introduction of negative interest rates would cause shorter‑ and longer‑term gilt yields to fall. Based on the experience of other countries, we believe this indeed is likely to occur. It would also increase the likelihood of negative nominal gilt yields, particularly at shorter maturities. Such a fall would, in the absence of a decrease in inflation expectations, also lead to real yields falling further.

When building investment portfolios, gilts and other high‑quality government bonds play important roles for many investors. One of these roles is to generate income. Clearly, gilt yields at or even below zero will not be positive news for investors looking to construct lower‑risk income portfolios. Income‑seekers may need to opt for riskier sources of income, rather than gilts.

Holdings gilts is also important to add resilience to portfolios—in particular, cushioning losses from more economically exposed, risky assets elsewhere in the portfolio. Government bonds or high‑quality corporate bonds have often acted as a shock absorber in times of market volatility as investors seek safety. For UK investors, the comfort that the UK government stands behind such instruments, as well as the lack of overseas currency exposure, mean they are effectively the most conservative building block for multi‑asset portfolios. Gilt yields at zero or below would reduce the cushion that such holdings would offer in bouts of market turbulence.

While short‑term rates may be set below zero by the BoE, we do not expect gilt yields to fall far into negative territory. No major central bank has yet set rates below ‑0.75% as the negative knock‑on impacts would be likely to outweigh policy objectives around these levels. This effectively creates a ‘floor’ for the government bond yield curve. It is instrumental to compare the falls in French, German and Japanese bond yields over the market turmoil in February and March 2020 with those of other, higher yielding government bonds that are often seen as safe‑havens.

Lower-Yielding Government Bonds Offered Less Protection in Early 2020

(Fig. 4) No major central bank has set rates below -0.75%

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Yields on generic 10‑year government bonds for each market. For illustrative purposes only.

As of 30 November 2020.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P.

In an environment where the BoE had also engaged in a negative rates regime, we believe the amount of diversification and risk mitigation that gilts would bring to multi‑asset portfolios would be limited. This should lead investors to consider whether identifying other ways for diversification would be required.

Options could include moving into other low‑risk but higher‑yielding assets such as global government bonds with their currency hedged to sterling; adding exposure to safe‑haven currencies such as the Japanese yen, Swiss franc and US dollar and considering other diversifying strategies such as gold or approaches more reliant on investment manager skill. A combination of a number of these approaches could be a way to ‘diversify the diversifiers’. Another possible approach would be to increase the allocation to less risky assets at the expense of riskier ones. Over the long term, however, this is likely to result in a fall in overall portfolio returns.

A move to negative interest rates would also impact investors who use short‑term cash holdings for capital protection or as a temporary holding for funds awaiting investment. Again, looking to euro markets as an example, the returns on short‑dated money market funds have now generally been negative for several years. This means investors must either increase risk in order to generate a positive return or accept a capital loss over the life of such holdings.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

This material is being furnished for general informational and/or marketing purposes only. The material does not constitute or undertake to give advice of any nature, including fiduciary investment advice, nor is it intended to serve as the primary basis for an investment decision. Prospective investors are recommended to seek independent legal, financial and tax advice before making any investment decision. T. Rowe Price group of companies including T. Rowe Price Associates, Inc. and/or its affiliates receive revenue from T. Rowe Price investment products and services. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. The value of an investment and any income from it can go down as well as up. Investors may get back less than the amount invested.

The material does not constitute a distribution, an offer, an invitation, a personal or general recommendation or solicitation to sell or buy any securities in any jurisdiction or to conduct any particular investment activity. The material has not been reviewed by any regulatory authority in any jurisdiction.

Information and opinions presented have been obtained or derived from sources believed to be reliable and current; however, we cannot guarantee the sources’ accuracy or completeness. There is no guarantee that any forecasts made will come to pass. The views contained herein are as of the date noted on the material and are subject to change without notice; these views may differ from those of other T. Rowe Price group companies and/or associates. Under no circumstances should the material, in whole or in part, be copied or redistributed without consent from T. Rowe Price.

The material is not intended for use by persons in jurisdictions which prohibit or restrict the distribution of the material and in certain countries the material is provided upon specific request. It is not intended for distribution to retail investors in any jurisdiction.

December 2020 / INVESTMENT INSIGHTS