November 2023 / FIXED INCOME

New long-term bank debt to expose holders to equity-like risk

From the Field

Key Insights

- Regulators have proposed new rules that would require U.S. banks with assets between USD 100 billion and USD 700 billion to issue new long-term senior unsecured debt.

- If passed as proposed, these regulations would bring U.S. regional bank debt issuance needs closer to the “big six” U.S. banks.

- However, we believe this type of debt subordinates holders and shifts the return profile of the debt to reflect equity-like risk with bond-like returns.

- Bottom-up credit research and active management will be critical in evaluating these risks and the prices of long-term bank debt.

Post-global financial crisis (GFC) bank regulation has largely focused on ending the “too big to fail” problem. During the GFC, authorities were forced to bail out banks that posed systemic risks due to their size, interconnectedness, and complexity. Bank regulations attempt to tackle the too-big-to-fail issue from two angles—reducing the probability of default and reducing systemic consequences of a bank that does fail.

Here we focus on measures intended to reduce the consequences of a bank that does fail.

The “bail in” framework for resolution of a failed bank

Regulators settled on a bail in framework, which has two critical components: the method of bank resolution and the stakeholders who have losses imposed upon them. The examples below provide a simplified illustration of what a hypothetical bank failure would look like:

The structure of a bank in resolution

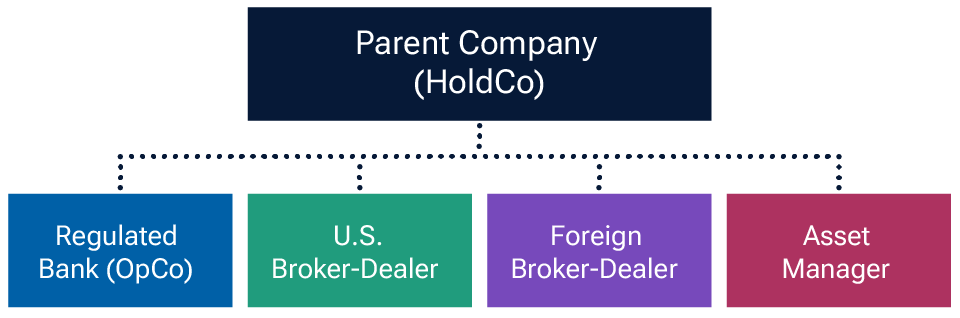

(Fig. 1) Regulators aim to keep OpCo open and stabilized.

Source: T. Rowe Price.

Method of resolution: Regulators favor the single point of entry (SPOE) resolution strategy. This is where the failure of the regulated bank operating company (OpCo)—one of the four subsidiaries in Figure 1—is addressed by putting the parent company (HoldCo) into bankruptcy or resolution and using HoldCo resources to recapitalize the failed OpCo, which has the following implications:

- This aims to keep the OpCo stabilized, out of bankruptcy, and open for business.

- Importantly, this framework assumes that OpCo creditors (short-term debt such as deposits and repo financing) remain in place, while HoldCo creditors are “bailed in.”

- Ultimately, this means that HoldCo creditors are used to stabilize the OpCo, and their bond holdings effectively become equity.

Actors who have losses imposed upon them: For the resolution strategy to work, there must be sufficient resources at the HoldCo that can be used to recapitalize the failed OpCo.

In a bid to avoid the use of public funds (either through a bail-out or through the FDIC’s deposit insurance fund), regulators want these resources to come from public investors.

Regulators define these resources as “total loss-absorbing capacity” (TLAC).

TLAC includes common equity, preferred equity,1 subordinated debt, and—perhaps most importantly—long-term senior unsecured debt. For HoldCo debt to qualify as TLAC, it must have at least one year to maturity, and it only receives full TLAC credit when it has at least two years to maturity.

Large regional banks would have to boost long-term debt issuance

There are two important differences between the above hypothetical bank failure and how a U.S. regional bank would likely be resolved:

1. Regional banks tend to be much simpler than their G-SIB2 counterparts. Regulators at the FDIC estimate that 75% of the banks affected by these new regulations keep an average of 97% of their assets at a single OpCo—the bank. As a result, it is much more likely that a bank failure would occur at the bank OpCo, meaning that loss‑absorbing resources need to sit at the OpCo and not at the HoldCo. In the words of FDIC Vice Chair Travis Hill, “long-term debt we care about needs to be at the bank—and only at the bank.”

2. In their “living wills” (documents that outline how a bank plans to be resolved in failure), regional banks currently adopt a multi-point-of-entry (MPOE) resolution strategy versus the SPOE strategy described above. Although they have been given the choice between SPOE and MPOE when creating their living wills, we believe that the introduction of long-term debt requirements means that regional banks are under a de facto SPOE resolution framework.

Although we do not anticipate further bank failures after the regional banking crisis of March 2023, regulators have proposed that U.S. banks with assets greater than USD 100 billion be required to issue new long‑term senior unsecured debt. This would bring their debt issuance requirements closer to the largest money center banks. While the proposal is still subject to industry feedback, we believe it is very likely to be implemented in 2024. These large regional banks would then need to increase their long-term debt issuance by about 25%, or approximately USD 70 billion,3 within three years.

Debt takes on equity-like risk

We believe that this bank resolution framework injects equity-like risk into the debt profile of U.S. banks.

To illustrate, consider the typical bank failure under the SPOE framework. Creditors of the bank OpCo are protected, while creditors of the HoldCo are bailed in. The OpCo creditors are generally derivative counterparties to the failed bank’s broker‑dealer subsidiary, depositors, or holders of commercial paper4 or repurchase agreements.5 Aside from depositors and commercial paper holders, these are often investors that use leverage.

On the other hand, the Federal Reserve has said “it is desirable that the holding company’s creditors be limited to those entities that can be exposed to losses without materially affecting financial stability,” typically meaning unlevered investors such as mutual funds and pension funds. This tiering between levered investors that are OpCo creditors (who are protected) and unlevered investors that are HoldCo creditors (who are not protected) subordinates holders of senior unsecured debt.

Also, because TLAC-qualifying HoldCo debt must have at least one year to maturity, this debt is effectively subordinated twice—first, because of its structural subordination to all OpCo debt and, second, because of its structural longer maturity than OpCo debt (the HoldCo is prohibited from issuing short‑term debt to external investors).

Transfer of value from bondholders to equity holders and the FDIC

The effect of this subordination is to explicitly codify HoldCo senior unsecured debt as a loss-absorbing resource (along with equity) that can be used to recapitalize a bank that has failed. By forcing banks to issue long-term senior unsecured debt, bank regulators are “economizing” scarce and expensive equity capital—and, in the process, allowing banks to hold less equity capital and more debt. This is a transfer of value from bondholders to equity holders.

Similarly, the subordination also reduces the risk to the FDIC’s Deposit Insurance Fund. Consider the failures earlier this year of several large regional banks. None of these banks were subject to long‑term debt requirements and so lacked sufficient resources that could be bailed in. One estimate of this cost calculated by academics at Yale University is USD 13.6 billion6—an expense that could have been avoided with the presence of long-term debt. FDIC Chairman Martin Gruenberg has indicated a clear desire for long-term debt to absorb losses before the FDIC.

What is a sufficient premium for heightened risk?

While there is nothing inherently wrong with subordination, it is important that HoldCo creditors demand a sufficient premium for this heightened risk. The question is, how much of a premium should HoldCo creditors demand relative to OpCo creditors and equity? Clearly, the risk premium should lie somewhere between OpCo debt and equity, but the market will determine this price.

In a world where risk in the financial system is low, the likelihood of bail-in is low and restricted to idiosyncratic developments in individual banks. In a world where risk in the financial system is high, the likelihood of a bail-in rises. In this situation, long-term HoldCo debt would increasingly resemble equity in likely becoming the fulcrum security that would bear significant losses.

Credit research, active management critical in evaluating risk

Bottom-up credit research and active management will be critical in evaluating these risks and the prices of long-term bank debt. Are we being paid sufficiently to own subordination risk? Which banks are the furthest from default? Is bank debt even appropriate for an investment-grade bond portfolio? These are the types of questions we will need to address when analyzing a debt instrument that may be subject to equity-like risks at the exact same time that overall risks in the financial system may be high.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

This material is being furnished for general informational purposes only. The material does not constitute or undertake to give advice of any nature, including fiduciary investment advice, and prospective investors are recommended to seek independent legal, financial and tax advice before making any investment decision. T. Rowe Price group of companies including T. Rowe Price Associates, Inc. and/or its affiliates receive revenue from T. Rowe Price investment products and services. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. The value of an investment and any income from it can go down as well as up. Investors may get back less than the amount invested.

The material does not constitute a distribution, an offer, an invitation, a personal or general recommendation or solicitation to sell or buy any securities in any jurisdiction or to conduct any particular investment activity. The material has not been reviewed by any regulatory authority in any jurisdiction.

Information and opinions presented have been obtained or derived from sources believed to be reliable and current; however, we cannot guarantee the sources' accuracy or completeness. There is no guarantee that any forecasts made will come to pass. The views contained herein are as of the date noted on the material and are subject to change without notice; these views may differ from those of other T. Rowe Price group companies and/or associates. Under no circumstances should the material, in whole or in part, be copied or redistributed without consent from T. Rowe Price.

The material is not intended for use by persons in jurisdictions which prohibit or restrict the distribution of the material and in certain countries the material is provided upon specific request.

It is not intended for distribution to retail investors in any jurisdiction.

Canada—Issued in Canada by T. Rowe Price (Canada), Inc. T. Rowe Price (Canada), Inc.’s investment management services are only available to Accredited Investors as defined under National Instrument 45-106. T. Rowe Price (Canada), Inc. enters into written delegation agreements with affiliates to provide investment management services.

© 2023 T. Rowe Price. All rights reserved. T. ROWE PRICE, INVEST WITH CONFIDENCE, and the bighorn sheep design are, collectively and/or apart, trademarks or registered trademarks of T. Rowe Price Group, Inc.

November 2023 / GLOBAL EQUITIES