February 2022 / RETIREMENT

Plan Sponsor, Plan Sponsor, Make Me a Match

Savings behavior impacts glide paths more than DC match formulas.

Key Insights

- Our modeling work found that participant savings behavior had a greater impact on glide path design than employer match generosity did.

- The richness of the match formula shifted the optimal glide path equity allocation by less than 5% at all ages, even in the absence of a defined benefit plan.

- These findings support the idea that participants ultimately own their outcomes when their retirements are supported primarily by defined contribution plans.

The preceding paper in our Benefit Connection series explored how different defined benefit (DB) designs can impact the target date glide path in an accompanying defined contribution (DC) plan. We showed how cost‑of‑living adjustments, lump‑sum availability, and benefit accrual patterns all can materially impact glide path design in various ways.1

While DC plans also may include a wide array of design features—such as auto‑enrollment, auto-escalation, and the specific investment lineup offered, just to name a few—the employer match is the feature we are most frequently asked about in relation to glide path appropriateness.

Employer contributions also can take many forms, but the advantage of a match formula is that it tends to promote better participant savings behavior and thus may result in higher account balances over time. Matching also is the most common contribution feature for the plans on T. Rowe Price’s recordkeeping platform. In this paper, we review how three different employer match formulas influenced the optimal glide path design in our modeling analysis.2

Plan design assessment

To assess how much glide paths should change based on various match formulas, we modeled four hypothetical plan designs, including the baseline safe harbor plan that we have used so far in the Benefit Connection series.

- Baseline: The employer matches 100% of the first three percentage points of employee salary deferrals and 50% of the next two percentage points, for a maximum employer contribution of 4% of salary.

- Lean: The employer matches 50% of the first four percentage points in salary deferrals, for a maximum employer contribution of 2% of salary.

- Average: The employer matches 50% of the first six percentage points in salary deferrals, for a maximum employer contribution of 3% of salary.

- Rich: The employer matches 100% of the first six percentage points in salary deferrals, for a maximum employer contribution of 6% of salary.

The lean, average, and rich designs collectively composed nearly half of the match formulas offered by the plans on our recordkeeping platform, with the average formula being the most common. We believe these designs represent a reasonable range in employer generosity—while acknowledging that there are match formulas that are leaner or richer than the ones modeled in our analysis.

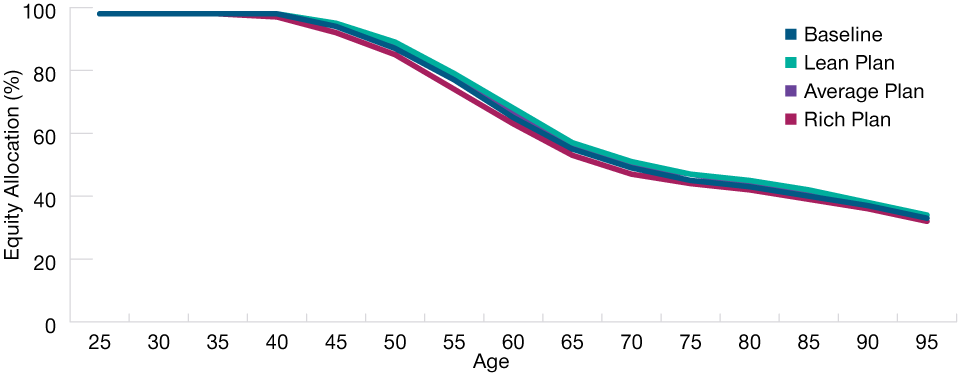

Match Generosity Had Minimal Impact on Glide Path Equity

(Fig. 1) Glide paths for hypothetical DC plans with varying match formulas

Source: T. Rowe Price.

For illustrative purposes only. Not representative of an actual investment or T. Rowe Price product. This analysis contains information derived from a Monte Carlo simulation. See Appendix for additional important disclosures.

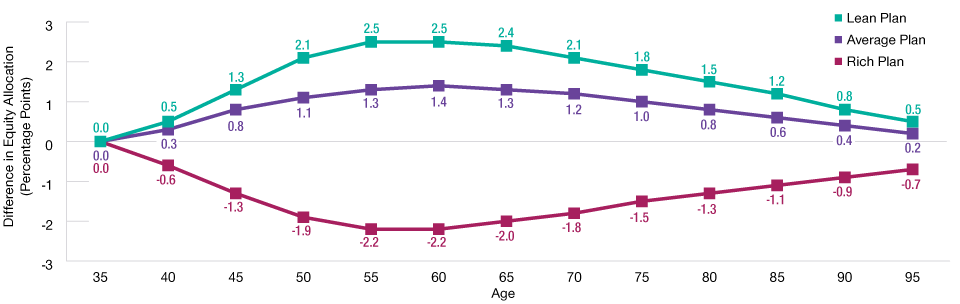

Only Minor Variations in Optimal Glide Path Equity Levels

(Fig. 2) Change in hypothetical equity allocations relative to baseline plan

Source: T. Rowe Price.

For illustrative purposes only. Not representative of an actual investment or T. Rowe Price product. This analysis contains information derived from a Monte Carlo simulation. See Appendix for additional important disclosures.

Figure 1 shows the hypothetical glide paths that our model identified as optimal for the four designs. Equity allocations in the lean and average glide paths were slightly above the baseline design. However, the maximum difference at any age was only 2.5 percentage points or less (Figure 2). The rich glide path featured slightly lower equity levels at age 40 and above, reflecting less need for participants in those plans to assume market risk to meet their retirement income targets, given their higher overall savings.

Overall, the maximum equity allocation difference (between the rich and the lean glide paths) was less than five percentage points at all ages. These relatively minor differences may be surprising, given that the match formula typically has the most impact on the cost of a plan. However, as we shall see, it does not necessarily have a major influence on glide path appropriateness when the match is altered in isolation.3

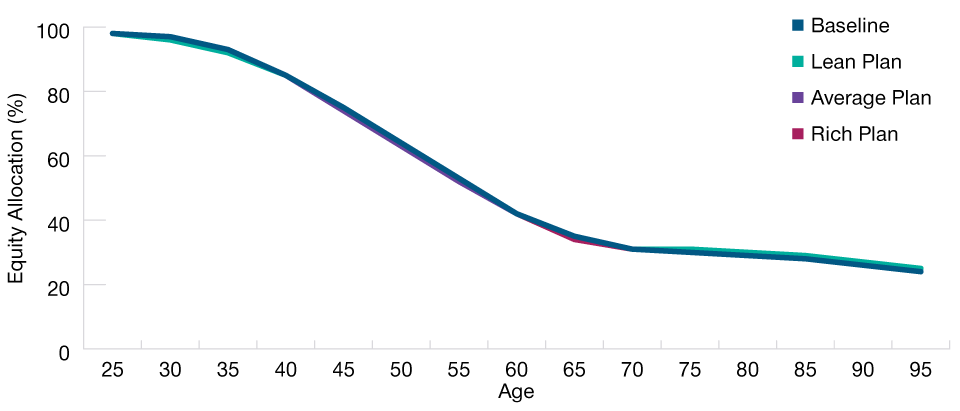

Even Less Impact When Paired With a Hypothetical DB Plan

(Fig. 3) Glide paths for hypothetical DC plans with varying match formulas

Source: T. Rowe Price.

For illustrative purposes only. Not representative of an actual investment or T. Rowe Price product. This analysis contains information derived from a Monte Carlo simulation. See Appendix for additional important disclosures.

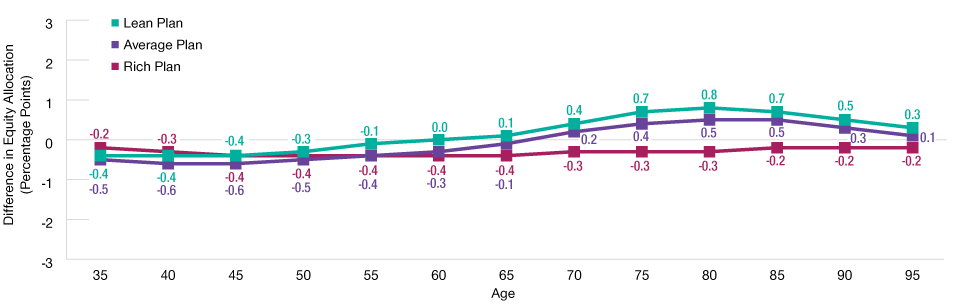

DB Plan Income Further Reduced Variations in Glide Path Equity

(Fig. 4) Change in hypothetical equity allocations relative to baseline plan

Source: T. Rowe Price.

For illustrative purposes only. Not representative of an actual investment or T. Rowe Price product. This analysis contains information derived from a Monte Carlo simulation. See Appendix for additional important disclosures.

In our models, the impact of different match formulas on the optimal glide path was even further muted when the DC plan was paired with an accompanying final average pay DB plan (Figures 3 and 4), because the participant income provided by the DB plan made the employer’s DC plan contributions an even smaller share of total retirement wealth.

This result only would have been reinforced if our model had reflected the reality that plan sponsors seeking to preserve liquidity have greater discretion to suspend their DC match formulas than to avoid the regulatory required minimum contributions for corporate DB plans or legislated funding requirements for some public DB plans. Throughout the 2008–2009 global financial crisis and more recently during the coronavirus pandemic, we saw several companies take advantage of this flexibility.

Even when we applied the same DC match formula across the entire length of an employee’s career, it still did not materially affect the optimal glide path in our model. A temporary suspension in the employer match would have reduced this impact even further.

Why the surprising results?

Higher Savings Reduced the Impact of Match Generosity

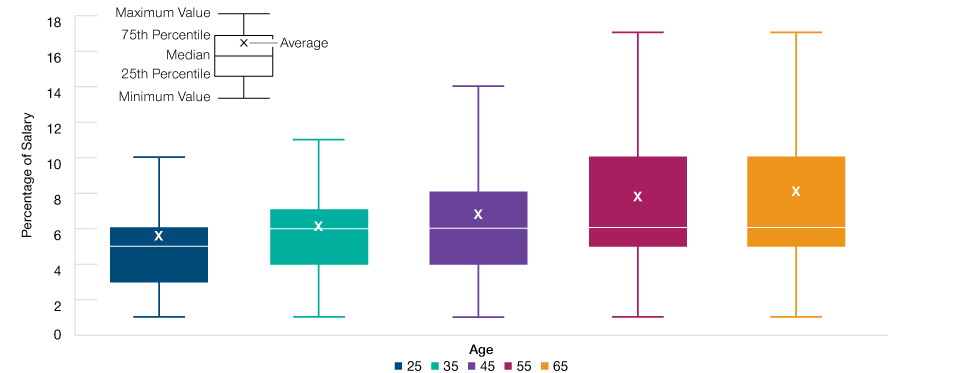

(Fig. 5) Distribution of salary deferral rates by age, 10,000 simulations

Source: T. Rowe Price.

T. Rowe Price recordkeeping data indicate that most plan participants respond rationally to incentives over their careers, meaning they start by saving at least as much as is required to maximize the employer match and then increase their salary deferrals as they age. Increased plan use of auto‑enrollment and auto‑escalation features probably has helped reinforce this behavior, which also is incorporated in our analysis (Figure 5).

Recently, we’ve seen renewed sponsor interest in further encouraging participant savings by stretching a lower match percentage to cover a higher percentage of salary deferral—for example, by offering to match 50% of the first 8% of salary rather than 100% of the first 4%.

Match formula design changes, in isolation, seemed to have minimal impact on the optimal glide path equity allocations indicated in our model. While we did not explicitly model the impact of different match designs on employee savings behavior, this is an area of research that we think warrants further exploration—particularly the impact of match formulas that require employees to defer a higher salary percentage to receive the full match.

In the population set we assumed for this paper—based on data from T. Rowe Price’s recordkeeping platform as of 2020—70% of participants started out saving at least 4% of salary and 50% started out saving at least 5%. By age 30, more than 50% of participants were deferring at least 6% of salary, a level that maximized the employer contributions in all the plans we modeled.

In the designs we modeled, the difference in the maximum employer contribution between the rich and lean plans was only 4% of salary (ranging from 2% to 6%), whereas the average participant deferral varied between 5.6% and 8.1% of salary, depending on age.4 Viewed through this lens, it’s not surprising that match generosity had a relatively small impact on optimal equity levels in the hypothetical plans we modeled. Most participants were deferring more than the employer match over most of their careers. This suggests that even when a plan sponsor cannot afford a generous match, there still may be opportunities to improve retirement outcomes by implementing auto features and incentivizing participant savings behavior. 5

Conclusions

While employers can prioritize matching contributions over other forms of compensation, our analysis indicates that participant behavior ultimately has the greatest impact on glide path equity allocations and on retirement readiness. Our recordkeeping data indicate that DC plan sponsors are having some success convincing participants of the importance of increasing savings, which ultimately reduces the standalone impact of the employer contribution on glide path design.

Important Information

This material is being furnished for general informational and/or marketing purposes only. The material does not constitute or undertake to give advice of any nature, including fiduciary investment advice. Prospective investors are recommended to seek independent legal, financial and tax advice before making any investment decision. T. Rowe Price group of companies including T. Rowe Price Associates, Inc. and/or its affiliates receive revenue from T. Rowe Price investment products and services. Past performance is no guarantee or a reliable indicator of future results.. The value of an investment and any income from it can go down as well as up. Investors may get back less than the amount invested.

The material does not constitute a distribution, an offer, an invitation, a personal or general recommendation or solicitation to sell or buy any securities in any jurisdiction or to conduct any particular investment activity. The material has not been reviewed by any regulatory authority in any jurisdiction.

Information and opinions presented have been obtained or derived from sources believed to be reliable and current; however, we cannot guarantee the sources’ accuracy or completeness. There is no guarantee that any forecasts made will come to pass. The views contained herein are as of the date written and are subject to change without notice; these views may differ from those of other T. Rowe Price group companies and/or associates. Under no circumstances should the material, in whole or in part, be copied or redistributed without consent from T. Rowe Price.

The material is not intended for use by persons in jurisdictions which prohibit or restrict the distribution of the material and in certain countries the material is provided upon specific request. It is not intended for distribution to retail investors in any jurisdiction.

USA—Issued in the USA by T. Rowe Price Associates, Inc., 100 East Pratt Street, Baltimore, MD, 21202, which is regulated by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. For Institutional Investors only.

© 2024 T. Rowe Price. All Rights Reserved. T. ROWE PRICE, INVEST WITH CONFIDENCE, and the Bighorn Sheep design are, collectively and/or apart, trademarks of T. Rowe Price Group, Inc.