February 2022 / FIXED INCOME

Predicting Tomorrow’s Megatrends

The rise of global bond investing

The rise of global investment-grade investing

One advantage of having 50 years in the fixed income business is watching markets grow from their infancy. One such market is the global investment-grade (IG) universe.

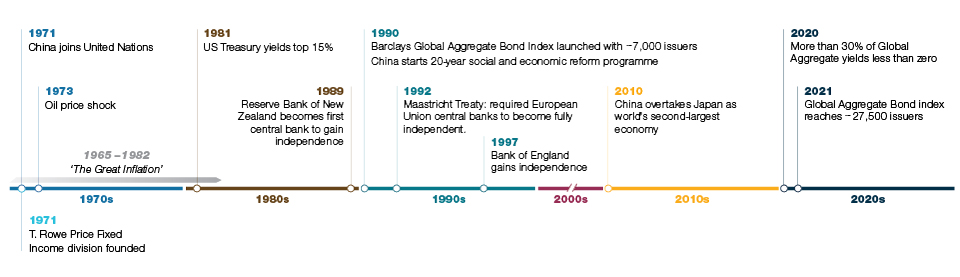

When T. Rowe Price set up its fixed income division in 1971, bond investing was a home-biased business: the average US or European investor had little reason to venture beyond the government bonds of their home country. It would be nearly two decades before the Bloomberg Global Aggregate Index was launched.

By the time I started investing in 1991, this soon-to-become-key benchmark contained about 7,000 issuers. Today, there are more than 27,000 names in the global IG toolkit. Let’s explore this growth, and draw some conclusions that could be relevant for future fixed income investing.

High yields in the 1970s and 80s

Towards the end of the 1970s, bond markets on both sides of the Atlantic deepened and broadened as interest rates became too high to ignore.

More than a decade of expansionary fiscal policy, with economic growth financed by government borrowing, together with the oil price shock of 1973/74 (which saw a 300% increase in oil prices) contributed to a surge in inflation. This resulted in a course correction by policymakers, and a move to monetarism as conceived by Milton Friedman: the idea that high interest rates were required to fight inflation.

The bond market took its cue from this change in economic policy orthodoxy, and bond yields soared: US Treasury yields topped 15% in 1981 and stayed high for the rest of the decade. Little did I realise, when I started my investing career, that we were in the early stages of a 30-year bull run.

The drive for central bank independence

Although fixed income returns had become competitive with equities, what bond markets lacked was transparency around policymaking. After the monetary turmoil of the 70s, the 1980s saw the rise of inflation targeting reinforced by monetarist doctrine, and this priority was reflected in a trend towards central bank independence. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand was granted independence in 1989, and over the course of the 1990s other countries followed suit.

Central bank independence created a framework for investors to commit. It allowed them to harness the value offered by high interest rates, because they had more confidence in monetary policy. As inflation targets were adopted more widely, both developed and emerging countries reaped the benefits of greater confidence in the ability to control inflation. This meant that yields fell, which meant borrowing costs became cheaper for governments, which meant the borrowing costs became cheaper for consumers, with significant knock-on benefits.

As it happened, just as central bank independence started to become more commonplace, inflation itself started to recede. It would be tempting to say that inflation receded because central banks had the independence to get on with the job, but that’s probably a sleight of hand, because what happened at this point was a phenomenal phase of globalisation. This meant that developed countries increasingly outsourced their labour-intensive, lower-value production to countries in developing markets. Especially, of course, to China.

Globalisation and the rise of China

In 1971, as T. Rowe Price was getting started in fixed income, China was becoming a member of the United Nations. 1980 marked the start of 20 years of socioeconomic reforms that grew China’s GDP to roughly the same size as California’s by the turn of the century.

By 2010, China had overtaken Japan as the world’s second-largest economy.

As China became more internationalist in its perspective, it also effectively became the workshop of the world and the ultra-competitive price-setter in many global goods markets. That globalisation effect brought down the marginal costs of production, and, therefore, the trend in goods inflation plummeted, becoming a persistent damper on inflation trends.

Looking forward

These three trends—better policy-making, central bank independence centred on inflation-targeting and the rise of global trade and pricing transparency—blended to create a golden age for bond investors. But the downside of the global bond rally has been a fall in yields to levels that would previously have been unthinkable. At one extreme, late 2020, more than a third of the Global Aggregate was yielding less than zero. Today, with a very different world as our starting point, what can we confidently predict about the coming decades?

The portfolio manager’s job today is a significantly more complex one. In a low-yield environment, the demands are greater in terms of research coverage and technology. Alpha generation depends more on the ability to identify and exploit relative value opportunities. Duration management requires more innovation and precision.

Efficient capital allocation requires more nuance and flexibility. Managers also need the technological infrastructure to meet client demands for integrating environmental, social and governance (ESG) analysis seamlessly into decision making, and for comparing and contrasting decisions on a consistent basis under ESG headings.

But if the challenges are greater, the toolkit is also much larger than it was, even a decade ago. The diversification opportunity has expanded exponentially across countries and debt sectors. Evolving derivative markets have broadened the toolkit for managing credit and other risks, and for adding exposure in more efficient and flexible ways.

In coming decades, globalisation won’t be the same unambiguous force for disinflation that it was in the past. We’ve seen a pullback by countries and companies from “peak globalisation”—for reasons ranging from political to pragmatic. For example, more companies have been “reshoring” elements of manufacturing because of rising costs or the availability of new technologies. “Just in time” is increasingly pushed aside in consideration of “just in case”.

Of course, higher inflation is not a one-way bet either. We will likely see new sources of deflationary pressure. One example may be greater use of robotic production. Another is demographic change: many countries—including China—are aging, and this could have a damping effect on price pressures.

It seems safe to predict that increasing awareness of ESG factors, in the durability of investments and the real embedded risks of making an investment decision, is going to be centre stage for at least the next generation. It’s no longer purely about market mechanisms, but also about self-imposed imperatives—notably the principle of preserving our environment.

This will involve potentially large adjustment costs, and the greater the imperative and the faster the progress, the higher the likelihood of inflationary frictions. Identifying the early-stage trends, and uncovering the less obvious winners and losers, will make the coming decade a fascinating time. And this means that, research-driven fixed income management skills will be even more imperative than they were 50 years ago.

Timeline: development of the global investment-grade opportunity

Risks

The following risks are materially relevant to the portfolio (refer to prospectus for further details):

ABS/MBS risk - these securities may be subject to greater liquidity, credit, default and interest rate risk compared to other bonds. They are often exposed to extension and prepayment risk. Contingent convertible bond risk - contingent convertible bonds have similar characteristics to convertible bonds with the main exception that their conversion is subject to predetermined conditions referred to as trigger events usually set to capital ratio and which vary from one issue to the other. Credit risk - a bond or money market security could lose value if the issuer’s financial health deteriorates. Currency risk - changes in currency exchange rates could reduce investment gains or increase investment losses. Default risk - the issuers of certain bonds could become unable to make payments on their bonds. Derivatives risk - derivatives may result in losses that are significantly greater than the cost of the derivative. Emerging markets risk - emerging markets are less established than developed markets and therefore involve higher risks. Interest rate risk - when interest rates rise, bond values generally fall. This risk is generally greater the longer the maturity of a bond investment and the higher its credit quality. Issuer concentration risk - to the extent that a portfolio invests a large portion of its assets in securities from a relatively small number of issuers, its performance will be more strongly affected by events affecting those issuers. Liquidity risk - any security could become hard to value or to sell at a desired time and price. Prepayment and extension risk - with mortgage- and asset-backed securities, or any other securities whose market prices typically reflect the assumption that the securities will be paid off before maturity, any unexpected behaviour in interest rates could impact portfolio performance. Sector concentration risk - the performance of a strategy that invests a large portion of its assets in a particular economic sector (or, for bond funds, a particular market segment), will be more strongly affected by events affecting that sector or segment of the fixed income market.

General portfolio risks

Capital risk - the value of your investment will vary and is not guaranteed. It will be affected by changes in the exchange rate between the base currency of the fund and the currency in which you subscribed, if different. Counterparty risk - an entity with which the portfolio transacts may not meet its obligations to the fund. ESG and Sustainability risk - may result in a material negative impact on the value of an investment and performance of the portfolio. Geographic concentration risk - to the extent that a portfolio invests a large portion of its assets in a particular geographic area, its performance will be more strongly affected by events within that area. Hedging risk - a portfolio’s attempts to reduce or eliminate certain risks through hedging may not work as intended. Investment fund risk - investing in portfolios involves certain risks an investor would not face if investing in markets directly. Management risk - the investment manager or its designees may at times find their obligations to a portfolio to be in conflict with their obligations to other investment portfolios they manage (although in such cases, all portfolios will be dealt with equitably). Operational risk - operational failures could lead to disruptions of portfolio operations or financial losses.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

This material is being furnished for general informational and/or marketing purposes only. The material does not constitute or undertake to give advice of any nature, including fiduciary investment advice, nor is it intended to serve as the primary basis for an investment decision. Prospective investors are recommended to seek independent legal, financial and tax advice before making any investment decision. T. Rowe Price group of companies including T. Rowe Price Associates, Inc. and/or its affiliates receive revenue from T. Rowe Price investment products and services. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. The value of an investment and any income from it can go down as well as up. Investors may get back less than the amount invested.

The material does not constitute a distribution, an offer, an invitation, a personal or general recommendation or solicitation to sell or buy any securities in any jurisdiction or to conduct any particular investment activity. The material has not been reviewed by any regulatory authority in any jurisdiction.

Information and opinions presented have been obtained or derived from sources believed to be reliable and current; however, we cannot guarantee the sources' accuracy or completeness. There is no guarantee that any forecasts made will come to pass. The views contained herein are as of the date noted on the material and are subject to change without notice; these views may differ from those of other T. Rowe Price group companies and/or associates. Under no circumstances should the material, in whole or in part, be copied or redistributed without consent from T. Rowe Price.

The material is not intended for use by persons in jurisdictions which prohibit or restrict the distribution of the material and in certain countries the material is provided upon specific request.

It is not intended for distribution to retail investors in any jurisdiction.