June 2023 / MARKETS & ECONOMY

The World Faces a Highly Variable Inflation Outlook

The US and UK face a tougher challenge than the Nordics and eurozone

Key Insights

- History shows that persistent inflation could potentially be avoided if countries adopt inflation targeting measures while deregulating product and labour markets.

- Our analysis suggests that countries in the Nordic area and the eurozone are likely best placed to avoid persistent inflation today.

- The more favourable inflation dynamics of the Nordics and eurozone suggest the bonds of these countries would likely provide a better medium‑term real yield return.

The inflation spike of the past two years has been the worst since the 1970s. Back then, its persistence caused central banks to tighten monetary policy for extended periods, fueling bouts of asset price volatility. In response, many countries introduced reforms designed to make future inflation surges easier to bring down. Did these reforms work—or could we be facing a repeat of 1970s‑style persistent inflation?

The reforms introduced following the experience of the 1970s included changes to product market regulations to foster more price competition for goods and services, monetary reforms that granted independence to central banks and set inflation as the sole target for monetary policy, and measures to encourage greater labour market participation and reduce second‑round wage inflation. The current bout of inflation is the biggest test these reforms have faced since their introduction.

To test how well they are likely to stand up to the challenge, we studied 89 inflation surges across 40 countries from 1970–2019. Our aim was to better understand which economic factors raise the risk of second‑round effects and greater inflation persistence. We define an inflation surge as an episode in which inflation is at least double its five‑year average value in a particular country.

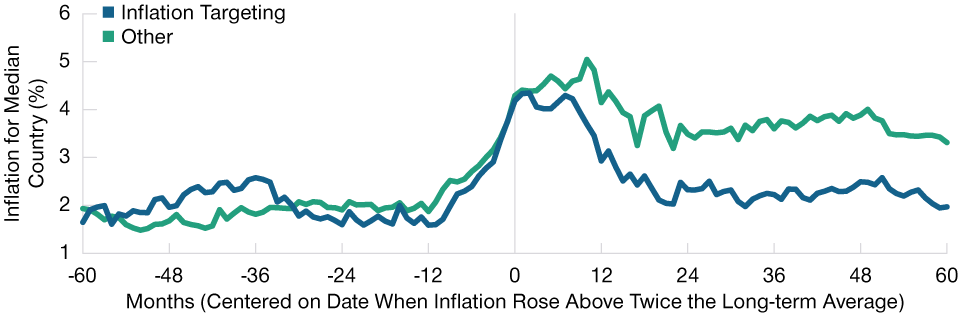

Our analysis shows that countries that adopted inflation targeting, deregulated labour and product markets, and had both high unemployment relative to history and high labour force participation relative to trend rates saw inflation return to previous long‑term averages within 16–22 months. Countries that did not adopt these measures, and that had low unemployment and low labour force participation rates, were more likely to see inflation persist over a longer period (Figure 1).

Inflation Targeting Policies Have Been Effective in the Past

(Fig. 1) Countries that adopt them bring inflation down more quickly

As of March 31, 2023.

The blue line shows median inflation outturns in countries that had adopted inflation targeting before the inflation surge. The green line shows outturns for countries with alternative monetary policy regimes. Long‑term average inflation is defined as the 5‑year average at time t=‑12 and has been scaled to 2% for illustrative purposes.

Sources: Cobham, David. “A comprehensive classification of monetary policy frameworks in advanced and emerging economies,” IMF, OECD, Haver, T. Rowe Price.

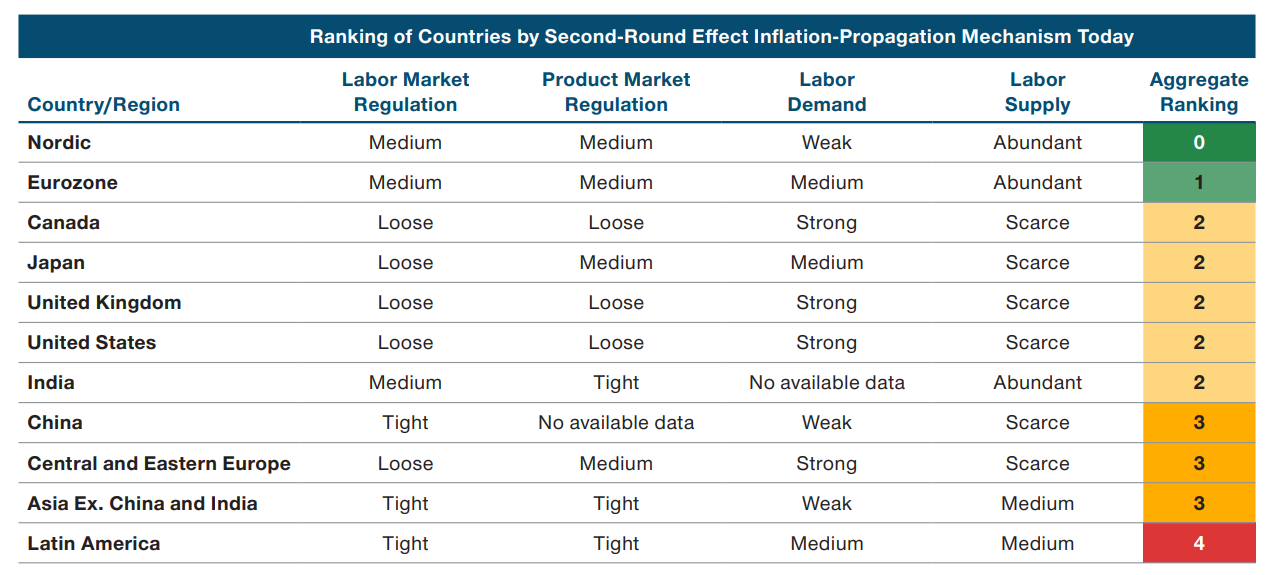

What does this imply for the path of inflation in different countries today? We ranked countries and regions across four factors: labour market regulation, product market regulation, labour demand, and labour supply (Figure 2). We found that the Nordic and eurozone regions are the least likely to experience persistent above‑target inflation because of strong labour supply (i.e., high labour force participation). Japan, the US, and the UK are more likely to experience above‑target inflation because of low labour force participation relative to trend. Emerging markets are most at risk of persistent inflation as these countries tend to have highly regulated product and labour markets in addition to labour market imbalances. Latin America, a region with a history of hyperinflation, has the highest risks of inflation persistence, according to our analysis. These results also hold true when Argentina is excluded, a country where year‑on‑year inflation was more than 100% in March.

Nordic and Eurozone Regions Least Likely to Suffer Persistent Inflation

(Fig. 2) Emerging markets most at risk

As of March 31, 2023.

Note: We use unemployment rate relative to long‑term average as our indicator of labor demand and the labor force participation rate as a deviation from trend as an indicator of labor supply. A high unemployment rate relative to long‑term average indicates weak labor demand, while a high labor force participation rate relative to trend indicates abundant labor supply. A higher number on the aggregate ranking reflects stronger propagation and second‑round inflation risks.Sources: IMF, OECD, Haver, T. Rowe Price.

These differences in expected inflation persistence will have consequences for monetary policies in these countries and regions. The Nordic area and eurozone, for example, should be able to cut policy rates earlier than other developed markets. In emerging markets, monetary policy may have to remain restrictive for longer to get inflation back under control.

Over the past year, bonds have sold off significantly in response to the inflation surge across the world. Our analysis suggests that inflation will be least persistent in the Nordic countries and the eurozone. This means that long‑term bonds in these regions are likely to experience the largest rally, since central banks there would likely be able to cut policy rates faster. Sovereign bonds of these countries with the most favourable inflation dynamics could potentially provide a better medium‑term real (inflation‑adjusted) yield return and also offer the potential for a larger capital gain. Conversely, inflation‑linked bonds could act as insurance against higher inflation in those developed markets more likely to experience persistent inflation, such as the UK.

In those emerging markets with the highest risk of high inflation persistence, our preference is hard currency‑denominated bonds. Several of these countries also face significant fiscal policy challenges and sometimes populist governments. In those countries, there is a risk of fiscal dominance, which means that central banks will likely be pressured to not hike interest rates to the levels necessary to return inflation back to their targets in the medium term. In these circumstances, local currency bonds are likely to underperform, which is why we prefer hard currency bonds instead.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

This material is being furnished for general informational and/or marketing purposes only. The material does not constitute or undertake to give advice of any nature, including fiduciary investment advice, nor is it intended to serve as the primary basis for an investment decision. Prospective investors are recommended to seek independent legal, financial and tax advice before making any investment decision. T. Rowe Price group of companies including T. Rowe Price Associates, Inc. and/or its affiliates receive revenue from T. Rowe Price investment products and services. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. The value of an investment and any income from it can go down as well as up. Investors may get back less than the amount invested.

The material does not constitute a distribution, an offer, an invitation, a personal or general recommendation or solicitation to sell or buy any securities in any jurisdiction or to conduct any particular investment activity. The material has not been reviewed by any regulatory authority in any jurisdiction.

Information and opinions presented have been obtained or derived from sources believed to be reliable and current; however, we cannot guarantee the sources' accuracy or completeness. There is no guarantee that any forecasts made will come to pass. The views contained herein are as of the date noted on the material and are subject to change without notice; these views may differ from those of other T. Rowe Price group companies and/or associates. Under no circumstances should the material, in whole or in part, be copied or redistributed without consent from T. Rowe Price.

The material is not intended for use by persons in jurisdictions which prohibit or restrict the distribution of the material and in certain countries the material is provided upon specific request.

It is not intended for distribution to retail investors in any jurisdiction.

June 2023 / INVESTMENT INSIGHTS