How to plan for housing and long-term care in the second half of retirement

December 2025, Make Your Plan

- Key Insights

-

- Housing choices in later retirement can have very different personal and cost implications, so it’s best to explore your options and have a plan in place before long‑term care (LTC) needs arise.

- While catastrophic LTC events are less widespread than many fear, budgeting for higher annual costs over a longer‑than‑usual period (one to five years) can have financial and psychological benefits.

- A thoughtful self‑funding plan can prove successful for a range of investors, but long‑term care insurance (LTCI) can help to protect a portion of assets and income if sustained medical and/or custodial care is needed.

Most people don’t want to burden their loved ones in older age and are inclined to spend less in retirement just in case they need long‑term care (LTC) one day. Yet few take the time to map out a plan for navigating the second half of retirement—and the physical and mental challenges that may accompany it. Whether planning for yourself or a parent, working together to develop a thoughtful aging plan can help reduce apprehension about spending freely in the healthier years of retirement and alleviate some of the shared worries about what’s next. Here are some key factors to consider when planning for a smooth transition into the mid-to-later years of retirement.

The personal: Housing and care choices

The housing and lifestyle choices you make can determine the LTC support options available to you, as well as the peace of mind you and your family may have along the way.

When aging in place means remaining at home

If you’d prefer to remain in your home, it’s important to plan for the logistics and establish support before unpaid bills stack up or you’re having mobility issues. While initially affordable and comfortable, it may become costly and emotionally taxing. Honest communication with loved ones about your changing needs is crucial.

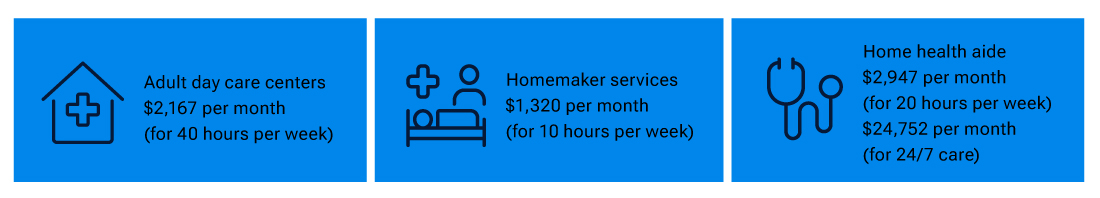

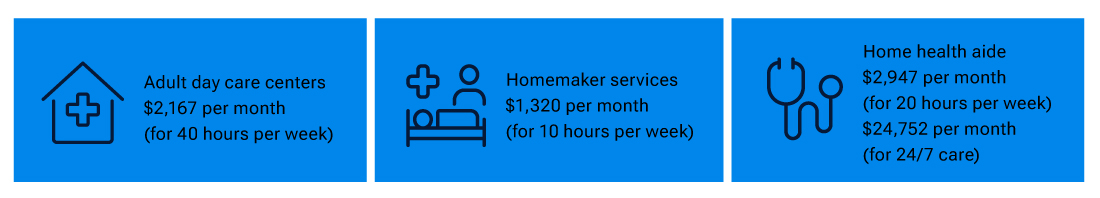

There are multiple support services available to help you age at home, but they vary in cost and care type. Adult day care centers and services can facilitate ongoing social interaction and provide respite for family caregivers. Homemaker services can assist with daily tasks such as meal preparation, errands, housekeeping, and transportation. Home health aides can provide custodial care and basic medical support in the comfort of a patient’s home. (See Figure 1.)

(Fig. 1) Median costs for services that help you age at home1

1 carescout.com/cost‑of‑care

close

close

When aging in place means proactively moving

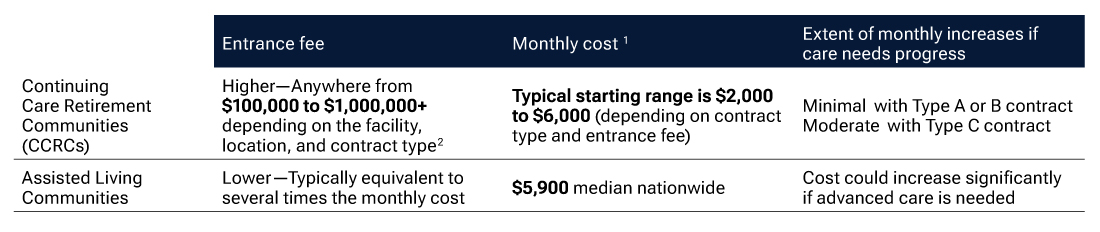

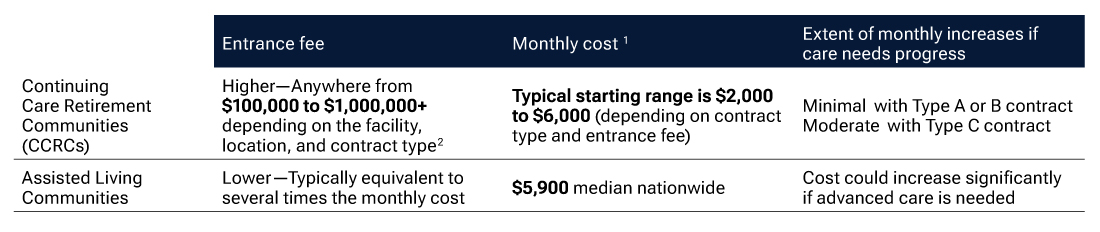

If you can afford to and are comfortable relocating, several options are available. Continuing care retirement communities (CCRCs) offer residents the contentment of knowing that all levels of care can be provided on‑site and all (or a good portion of) future medical expenses have been factored into the entrance fee and monthly payment. The ability to lock in a predictable monthly cost—which will not increase if care needs advance—make CCRCs an attractive option, especially for people with high concerns about needing LTC.

Assisted living communities are designed for older individuals who may eventually need assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs)1 but do not want to prepay for advanced LTC support they may never need. Compared with a CCRC, the entrance fee is minimal, but the monthly cost could increase substantially as care needs progress. (See Figure 2.)

It should be noted that if you opt to age at home or move into an assisted living community, declining health may necessitate relocation to a more extensive (and expensive) care environment such as a skilled nursing facility or nursing home—temporarily or indefinitely.

(Fig. 2) Key differences between CCRCs and assisted living communities

1 Monthly cost for both community types generally includes basic medical and custodial support, food, amenities, building maintenance, and staffing. Costs are subject to annual inflation adjustments.

2 There are generally three CCRC contract types: Type A plans typically include prepayment for all future care (custodial, memory care, etc.). Type B plans include a partial prepayment for future care. Type C plans are also known as pay‑for‑service contracts, meaning costs go up as care needs progress.

close

close

The financial: Estimating the costs of anticipated care

Many factors influence LTC costs, including housing choices, health and family medical history, location, and the availability of a spouse or adult child to provide intermittent, unpaid care. Since Medicare generally will not cover LTC costs and many individuals are unlikely to qualify for Medicaid,2 it’s helpful to start by forming an estimate for the cost and duration of care you may face.

Understanding out‑of‑pocket costs

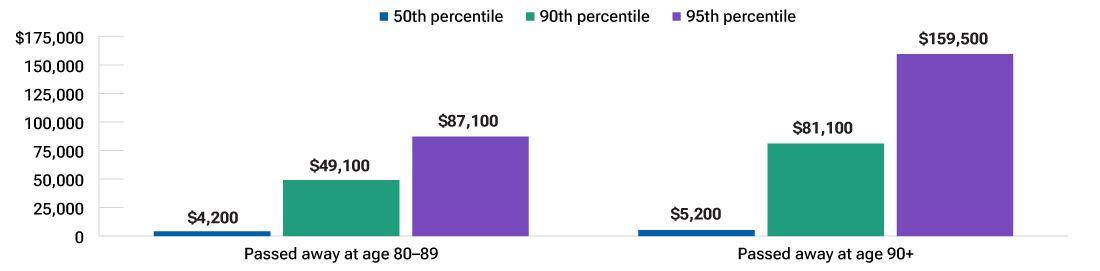

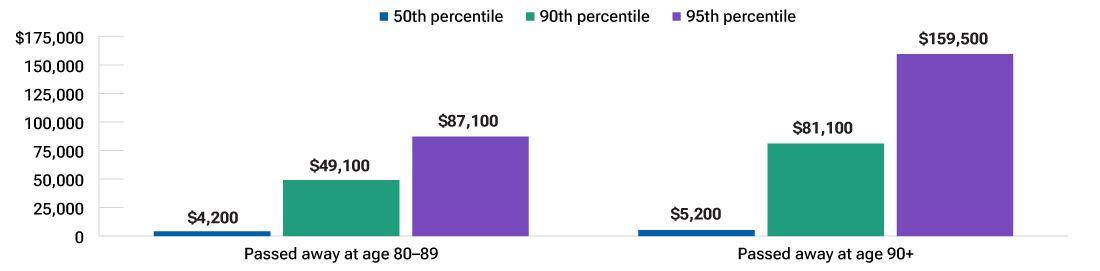

According to our analysis of data from the Social Security Administration‑sponsored Health and Retirement Study (HRS), out‑of‑pocket health care spending tends to increase sharply at end of life.3 But the financial impact is more concentrated and less widespread than many assume. Among the population with the highest out‑of‑pocket expenses4 (age 90+), 50% spent less than $5,200 per year. And only 5% faced truly catastrophic costs above $159,500. (See Figure 3.)

When it comes to LTC facility stays, nearly 50% of individuals who died after age 65 didn’t require entry into a LTC facility. Roughly 25% needed facility‑provided support for less than three months and only 14% had stays exceeding one year.

Annualized out‑of‑pocket health care spending in final year of life

(Fig. 3) Spending tends to increase at end of life and is generally higher for those who die at older ages.

Source: Banerjee, Sudipto, “How unpacking heath care expenses can empower retirement savers,”

T. Rowe Price white paper, June 2025. T. Rowe Price’s calculations from the HRS, 2020 core and 2014–2020 exit surveys.

Note: All expenses are rounded to the nearest hundred and adjusted to 2024 dollars.

close

close

Guidance for estimating costs

While relatively few people spend over a year in a nursing home or incur annual LTC costs above $90,000, planning for these higher‑risk scenarios can prove financially and psychologically beneficial, especially considering that care needs often escalate gradually. A moderate approach might involve budgeting for one to two years of 90th percentile out‑of‑pocket costs ($80,000 to $90,000 per year). If you plan on relocating to a CCRC or moving in with an adult child who has agreed to care for you, you may be able to budget for lower additional costs. If you plan on receiving full‑time care at home, you might need to budget more.

The planning: Evaluating strategies to pay for LTC

If you are unlikely to qualify for LTC through Medicaid, the choice often comes down to self‑funding and/or purchasing long‑term care insurance (LTCI). Advocates of LTCI argue that it can reduce the need for an elderly individual (or their family members) to settle for a patchwork of low‑cost services when better, more expensive care is warranted. Others argue that the risk of paying high premiums and never needing care or facing roadblocks for approval of benefits make insurance less attractive than self‑funding.

Long‑term care insurance (LTCI)

LTCI can help to protect a portion of your assets and income in the event of a sustained care need. Since lack of knowledge is often a driver for not considering or having LTCI, here are some key items to understand in order to make a more informed decision:

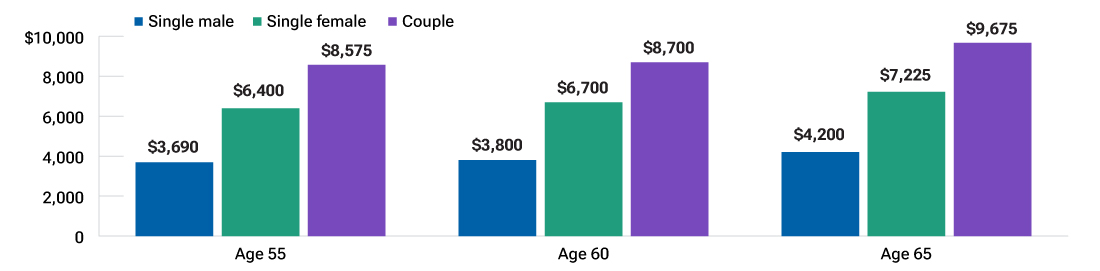

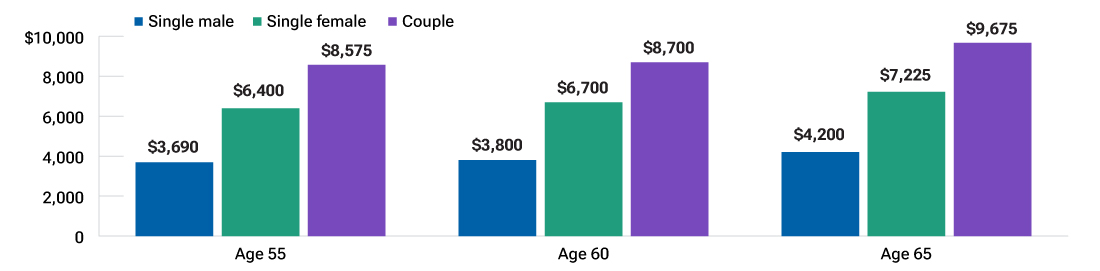

- If a policy makes sense for your situation, a good time to purchase it is between ages 55 and 65. Denial rates for applications increase after age 65.5

- Most policies offer a set term (typically three to five years) or a specific lifetime benefit amount. While lifetime (unlimited) payout policies are no longer available, a policy with a three‑ to five‑year benefit period, a generous daily maximum, and inflation protection may make sense.

- Personal attributes (such as age, gender, health, and location) can affect LTCI premiums and approval. Premiums are generally higher for women.

- There are many policy‑related choices and key terms to understand. Most policy choices are decided up front and can affect the cost of premiums as well as the potential benefits you could realize from the policy. Two aspects are especially important to understand:

- Types of qualifying care: Policies with the broadest range of support types included (home health care, assisted living, skilled nursing, adult day care, physical therapy, etc.) are generally the most expensive, but preferable, since it’s hard to predict your needs many years in advance.

- Activities of daily living and benefit initiation eligibility: For an LTCI policy to begin paying benefits, the insured must demonstrate the inability to perform two or more of these activities without assistance. It’s prudent to seek a policy that defines cognitive impairment as a qualifying condition.

For additional guidance on terms to understand and factors to consider when weighing the costs and benefits of LTCI—as well as information about options such as hybrid policies and state partnership plans—see our comprehensive guide at troweprice.com/longtermcareguide.

Annual policy premium based on $165,000 initial lifetime benefit

(Fig. 4) Policy premium costs can vary widely, based on starting age and gender.

Source: aaltci.org/long‑term‑care‑insurance/learning‑center/ltcfacts‑2024.php

Assumes 5% annual compound benefit growth rate; select health; prices for state of Illinois and can vary by state. AALTCI calculations as of January 2024.

close

close

Self‑funding

Some individuals prefer to self‑fund and, based on their income, savings, and spending, may be in a good position to do so, even with several years of LTC expenses built in at the end of plan.

To build a successful self‑funding strategy (whether it includes LTCI or not), here are several key factors to consider:

- Account for how your spending may change over the course of retirement. While your expenses may remain relatively constant during the first half of your retirement, spending reductions later on may provide a cushion for any out‑of‑pocket LTC expenses incurred in the second half.

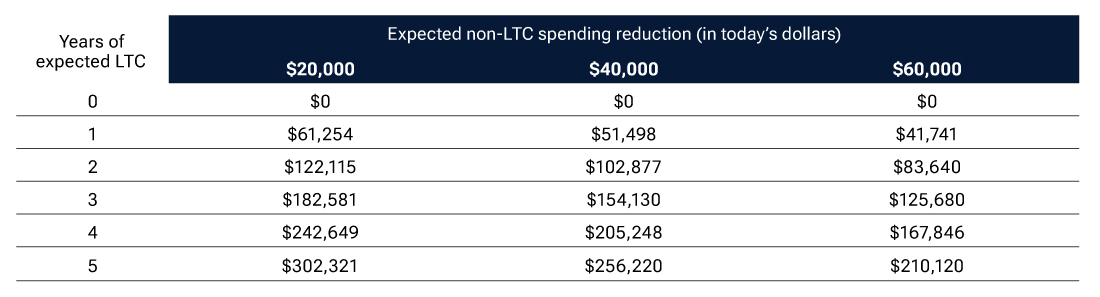

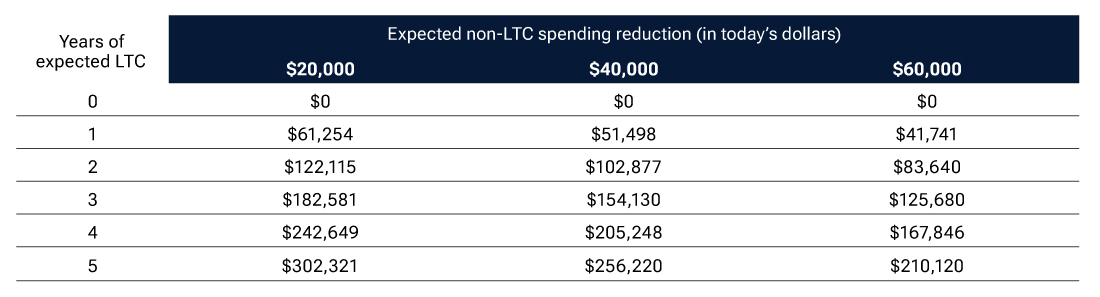

- Determine an amount to earmark for your LTC reserve—amount needed today to fund future LTC expenses, based on assumed investment return, other spending reductions, inflation rates, length and cost of care, and time until care is needed. (See Figure 5.)

- Consider earmarking account(s) for LTC needs. Once you’ve identified an LTC reserve goal, you can implement a plan to reach it. Also, you could consider investing those assets more aggressively in early and mid‑retirement, then dial back the risk over time.

- Maximize lifetime income sources (such as Social Security). Actions such as delaying Social Security can provide lifestyle protection if you live a very long life, whether you need LTC or not.

LTC reserve needed today to fund LTC starting in 25 years

(Fig. 5) Expected non‑LTC spending reductions can help determine an appropriate LTC reserve target.

Assumptions: LTC cost of $90,000 in today’s dollars. Inflation rate is 5% for LTC and 3% for all other spending. 6% average annual return on the LTC reserve pool. Source: T. Rowe Price calculations. The concept of calculating the present value of future dollars needed to cover LTC costs (adjusted for other spending reductions) is outlined in Pfau, Wade D., “Retirement Planning Guidebook: Navigating the Important Decisions for Retirement Success,” (2nd Edition), 2024, Retirement Researcher Media, Vienna, VA.

close

close

Advantages or disadvantages of LTCI vs. self‑funding

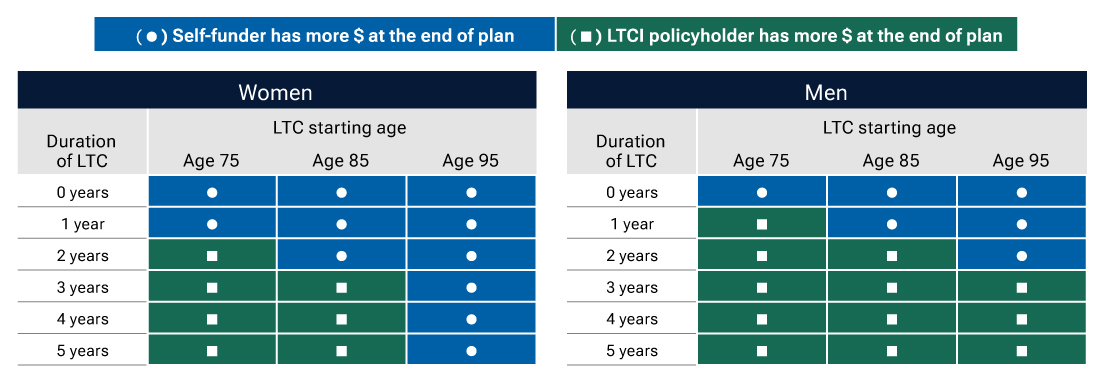

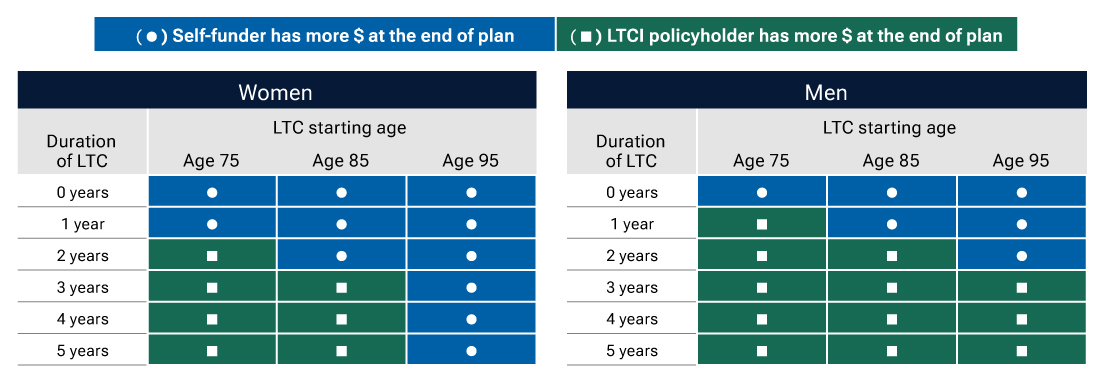

To better understand how the purchase of a standard LTCI policy might help protect an investor’s assets compared with self‑funding alone, we analyzed the trade‑off.6 We sought to understand the advantages or disadvantages of self‑funding compared with LTCI based on gender, starting age of care, and care duration.

We compared two men and two women, separately. All investors are age 60, have the same starting investment balance in their LTC reserve, and receive a 6% annual return. Within each gender pair, one person purchases LTCI and the other self‑funds. The self‑funding investors make no withdrawals until LTC is needed. The LTCI policyholders withdraw only the cost of the annual premium each year until LTC begins. The LTCI policy has a three‑year guarantee period and a $4,500 monthly maximum benefit with 3% compound inflation protection.

Armed with these assumptions, we ran scenarios that combined the duration of care needed with the age that care began.7 We then observed the ending balance differential for each gender group, depending on the timing and duration of their LTC needs. (See Figure 6.)

As you would expect, insurance works out better when care is needed longer. But insurance is also more beneficial if care is needed at an earlier age because fewer premium payments will have been made before benefits start. If care is needed for less than two years (or not needed), self‑funding usually has an advantage.

- The greatest LTCI advantage (the case with five years of LTC starting at age 75) was $102,000 and $137,000 for women and men, respectively.

- The greatest self‑funding advantage (the case with zero years of care and living to age 95) was $196,000 and $115,000 for women and men, respectively.

Ending balance advantage based on gender, starting age of care, and care duration

(Fig. 6) LTCI can help to protect one’s investments, especially when LTC is needed earlier and longer.

Assumptions: Residents of Virginia. Source for premium quotes and terms (obtained November 2025): mutualofomaha.com/long‑term‑care‑insurance/calculator. The male investor’s annual premium is $2,664; the female’s is $4,536; premiums remain constant until care is needed, at which point premiums are waived. The LTCI policy has a 3‑year guarantee period and a $4,500 maximum monthly benefit with 3% compound inflation protection. Annual LTC costs are greater than the LTCI maximum benefits (but the amount does not affect this comparison). Inflation rates are 5% on LTC expenses and 3% on all other spending. It is assumed that the investor passes away at the end of the care period. Amounts reflect the difference in ending investment balances in today’s dollars.

close

close

Other key factors: Because premiums are higher for women, the LTCI advantage for them tends to be less (or self‑funding advantage more) than for a man at a similar age with similar care needs. And of course, if the investment return were higher than our assumed 6% or LTCI premiums increased over time,8 self‑funding would look better.

Key takeaway

When it comes to LTC planning, it’s important to recognize that neither self‑funding nor LTCI can fully alleviate the potential pressure on your investment portfolio if you require prolonged support. Fortunately, the actual out‑of‑pocket expenses incurred by most people in the final two years of life—on services such as in‑home care, adult day care, and nursing home stays—are less severe than many people fear. Among the population with the highest out‑of‑pocket expenses (age 90+), 50% spent less than $5,200 per year. At the end of life, approximately 75% of individuals over age 65 (and not covered by Medicaid) either didn’t experience a LTC facility stay or spent less than three months.

These statistics suggest that for those who have planned and saved adequately, mapped out their spending over time, and closely considered their housing preferences and care options, self‑funding can prove successful. However, an LTCI policy might be worthwhile if your LTC risk is particularly high or if you value the peace of mind such policies can offer.

For more information, data, analysis, and practical guidance for navigating the uncertainties of the mid-to-later years of retirement, see our comprehensive guide: “Planning for life and long‑term care in the second half of retirement” at troweprice.com/longtermcareguide.

Lindsay Theodore, CFP®

Thought Leadership Senior Manager

Lindsay Theodore, CFP®

Thought Leadership Senior Manager

Roger Young, CFP®

Thought Leadership Director

Roger Young, CFP®

Thought Leadership Director

Want a personalized financial plan delivered by a T. Rowe Price Financial Advisor?

1 Activities of daily living are essential factors for initiating benefits and include bathing, dressing, toileting, continence, walking, transferring, and eating.

2 According to the American Council on Aging, to be eligible for LTC through Medicaid, a single 65‑year‑old individual generally must have income no greater than $34,812 per year and “countable assets” no greater than $2,000. These limits vary by state, age, disability, and marital status. Countable assets are liquid assets, such as bank savings, investments, and IRAs. medicaidplanningassistance.org/medicaid‑eligibility/

3 Banerjee, Sudipto, “How unpacking heath care expenses can empower retirement savers,” T. Rowe Price white paper, June 2025.

4 Health care premiums were excluded from out‑of‑pocket expenses because they are ongoing and predictable. Individuals covered by Medicaid were excluded from this analysis.

5 aarp.org/caregiving/financial‑legal/info‑2019/when‑to‑buy‑long‑term‑care‑insurance.html

6 "T. Rowe Price guide to planning for life and long‑term care in the second half of retirement,” pages 22–23. troweprice.com/longtermcareguide

7 In scenarios where no care is needed, the ages refer to the age at death.

8 For simplicity, we assumed LTCI premiums did not increase, but premiums can increase 30% or more over the life of the policy.

Important Information

This material is provided for informational purposes only and is not intended to be investment advice or a recommendation to take any particular investment action.

The views contained herein are those of the authors as of November 2025 and are subject to change without notice; these views may differ from those of other T. Rowe Price associates.

This information is not intended to reflect a current or past recommendation concerning investments, investment strategies, or account types; advice of any kind; or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any securities or investment services. The opinions and commentary provided do not take into account the investment objectives or financial situation of any particular investor or class of investor. Please consider your own circumstances before making an investment decision.

Information contained herein is based upon sources we consider to be reliable; we do not, however, guarantee its accuracy. Actual future outcomes may differ materially from any estimates or forward‑looking statements provided.

Past performance is no guarantee or reliable indicator of future results. All investments are subject to market risk, including the possible loss of principal. All charts and tables are shown for illustrative purposes only.

T. Rowe Price Investment Services, Inc., distributor. T. Rowe Price Associates, Inc., investment adviser. T. Rowe Price Investment Services, Inc., and T. Rowe Price Associates, Inc., are affiliated companies.

© 2025 T. Rowe Price. All Rights Reserved. T. ROWE PRICE, INVEST WITH CONFIDENCE, the Bighorn Sheep design, and related indicators (see troweprice.com/ip) are trademarks of T. Rowe Price Group, Inc. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners.

- 202511‑5012932